‘This is possibly the single largest design flaw contributing to the bad Nash equilibrium in which … many governments are stuck. Every individual high-functioning competent person knows they can’t make much difference by being one more face in that crowd.’ Eliezer Yudkowsky, AI expert, LessWrong etc.

‘[M]uch of our intellectual elite who think they have “the solutions” have actually cut themselves off from understanding the basis for much of the most important human progress.’ Michael Nielsen, physicist and one of the handful of most interesting people I’ve ever talked to.

‘People, ideas, machines — in that order.’ Colonel Boyd.

‘There isn’t one novel thought in all of how Berkshire [Hathaway] is run. It’s all about … exploiting unrecognized simplicities.’ Charlie Munger,Warren Buffett’s partner.

‘Two hands, it isn’t much considering how the world is infinite. Yet, all the same, two hands, they are a lot.’ Alexander Grothendieck, one of the great mathematicians.

*

There are many brilliant people in the civil service and politics. Over the past five months the No10 political team has been lucky to work with some fantastic officials. But there are also some profound problems at the core of how the British state makes decisions. This was seen by pundit-world as a very eccentric view in 2014. It is no longer seen as eccentric. Dealing with these deep problems is supported by many great officials, particularly younger ones, though of course there will naturally be many fears — some reasonable, most unreasonable.

Now there is a confluence of: a) Brexit requires many large changes in policy and in the structure of decision-making, b) some people in government are prepared to take risks to change things a lot, and c) a new government with a significant majority and little need to worry about short-term unpopularity while trying to make rapid progress with long-term problems.

There is a huge amount of low hanging fruit — trillion dollar bills lying on the street — in the intersection of:

- the selection, education and training of people for high performance

- the frontiers of the science of prediction

- data science, AI and cognitive technologies (e.g Seeing Rooms, ‘authoring tools designed for arguing from evidence’, Tetlock/IARPA prediction tournaments that could easily be extended to consider ‘clusters’ of issues around themes like Brexit to improve policy and project management)

- communication (e.g Cialdini)

- decision-making institutions at the apex of government.

We want to hire an unusual set of people with different skills and backgrounds to work in Downing Street with the best officials, some as spads and perhaps some as officials. If you are already an official and you read this blog and think you fit one of these categories, get in touch.

The categories are roughly:

- Data scientists and software developers

- Economists

- Policy experts

- Project managers

- Communication experts

- Junior researchers one of whom will also be my personal assistant

- Weirdos and misfits with odd skills

We want to improve performance and make me much less important — and within a year largely redundant. At the moment I have to make decisions well outside what Charlie Munger calls my ‘circle of competence’ and we do not have the sort of expertise supporting the PM and ministers that is needed. This must change fast so we can properly serve the public.

A. Unusual mathematicians, physicists, computer scientists, data scientists

You must have exceptional academic qualifications from one of the world’s best universities or have done something that demonstrates equivalent (or greater) talents and skills. You do not need a PhD — as Alan Kay said, we are also interested in graduate students as ‘world-class researchers who don’t have PhDs yet’.

You should have the following:

- PhD or MSc in maths or physics.

- Outstanding mathematical skills are essential.

- Experience of using analytical languages: e.g. Python, SQL, R.

- Familiarity with data tools and technologies such as Postgres, Scikit Learn, NEO4J.

A few examples of papers that you will be considering:

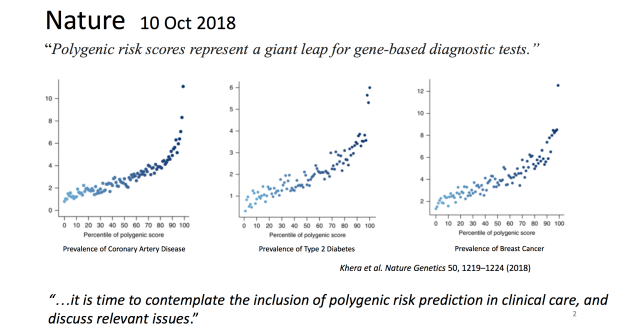

- This Nature paper, Early warning signals for critical transitions in a thermoacoustic system, looking at early warning systems in physics that could be applied to other areas from finance to epidemics.

- Statistical & ML forecasting methods: Concerns and ways forward, Spyros Makridakis, 2018. This compares statistical and ML methods in a forecasting tournament (won by a hybrid stats/ML approach).

- Complex Contagions : A Decade in Review, 2017. This looks at a large number of studies on ‘what goes viral and why?’. A lot of studies in this field are dodgy (bad maths, don’t replicate etc), an important question is which ones are worth examining.

- Model-Free Prediction of Large Spatiotemporally Chaotic Systems from Data: A Reservoir Computing Approach, 2018. This applies ML to predict chaotic systems.

- Scale-free networks are rare, Nature 2019. This looks at the question of how widespread scale-free networks really are and how useful this approach is for making predictions in diverse fields.

- On the frequency and severity of interstate wars, 2019. ‘How can it be possible that the frequency and severity of interstate wars are so consistent with a stationary model, despite the enormous changes and obviously non-stationary dynamics in human population, in the number of recognized states, in commerce, communication, public health, and technology, and even in the modes of war itself? The fact that the absolute number and sizes of wars are plausibly stable in the face of these changes is a profound mystery for which we have no explanation.’ Does this claim stack up?

- The papers on computational rationality below.

- The work of Judea Pearl, the leading scholar of causation who has transformed the field.

You should be able to explain to other mathematicians, physicists and computer scientists the ideas in such papers, discuss what could be useful for our projects, synthesise ideas for other data scientists, and apply them to practical problems. You won’t be expert on the maths used in all these papers but you should be confident that you could study it and understand it.

We will be using machine learning and associated tools so it is important you can program. You do not need software development levels of programming but it would be an advantage.

Those applying must watch Bret Victor’s talks and study Dynamic Land. If this excites you, then apply; if not, then don’t. I and others interviewing will discuss this with anybody who comes for an interview. If you want a sense of the sort of things you’d be working on, then read my previous blog on Seeing Rooms, cognitive technologies etc.

B. Unusual software developers

We are looking for great software developers who would love to work on these ideas, build tools and work with some great people. You should also look at some of Victor’s technical talks on programming languages and the history of computing.

You will be working with data scientists, designers and others.

C. Unusual economists

We are looking to hire some recent graduates in economics. You should a) have an outstanding record at a great university, b) understand conventional economic theories, c) be interested in arguments on the edge of the field — for example, work by physicists on ‘agent-based models’ or by the hedge fund Bridgewater on the failures/limitations of conventional macro theories/prediction, and d) have very strong maths and be interested in working with mathematicians, physicists, and computer scientists.

The ideal candidate might, for example, have a degree in maths and economics, worked at the LHC in one summer, worked with a quant fund another summer, and written software for a YC startup in a third summer!

We’ve found one of these but want at least one more.

The sort of conversation you might have is discussing these two papers in Science (2015): Computational rationality: A converging paradigm for intelligence in brains, minds, and machines, Gershman et al and Economic reasoning and artificial intelligence, Parkes & Wellman.

You will see in these papers an intersection of:

- von Neumann’s foundation of game theory and ‘expected utility’,

- mainstream economic theories,

- modern theories about auctions,

- theoretical computer science (including problems like the complexity of probabilistic inference in Bayesian networks, which is in the NP–hard complexity class),

- ideas on ‘computational rationality’ and meta-reasoning from AI, cognitive science and so on.

If these sort of things are interesting, then you will find this project interesting.

It’s a bonus if you can code but it isn’t necessary.

D. Great project managers.

If you think you are one of the a small group of people in the world who are truly GREAT at project management, then we want to talk to you. Victoria Woodcock ran Vote Leave — she was a truly awesome project manager and without her Cameron would certainly have won. We need people like this who have a 1 in 10,000 or higher level of skill and temperament.

The Oxford Handbook on Megaprojects points out that it is possible to quantify lessons from the failures of projects like high speed rail projects because almost all fail so there is a large enough sample to make statistical comparisons, whereas there can be no statistical analysis of successes because they are so rare.

It is extremely interesting that the lessons of Manhattan (1940s), ICBMs (1950s) and Apollo (1960s) remain absolutely cutting edge because it is so hard to apply them and almost nobody has managed to do it. The Pentagon systematically de-programmed itself from more effective approaches to less effective approaches from the mid-1960s, in the name of ‘efficiency’. Is this just another way of saying that people like General Groves and George Mueller are rarer than Fields Medallists?

Anyway — it is obvious that improving government requires vast improvements in project management. The first project will be improving the people and skills already here.

If you want an example of the sort of people we need to find in Britain, look at this on CC Myers — the legendary builders. SPEED. We urgently need people with these sort of skills and attitude. (If you think you are such a company and you could dual carriageway the A1 north of Newcastle in record time, then get in touch!)

E. Junior researchers

In many aspects of government, as in the tech world and investing, brains and temperament smash experience and seniority out of the park.

We want to hire some VERY clever young people either straight out of university or recently out with with extreme curiosity and capacity for hard work.

One of you will be a sort of personal assistant to me for a year — this will involve a mix of very interesting work and lots of uninteresting trivia that makes my life easier which you won’t enjoy. You will not have weekday date nights, you will sacrifice many weekends — frankly it will hard having a boy/girlfriend at all. It will be exhausting but interesting and if you cut it you will be involved in things at the age of ~21 that most people never see.

I don’t want confident public school bluffers. I want people who are much brighter than me who can work in an extreme environment. If you play office politics, you will be discovered and immediately binned.

F. Communications

In SW1 communication is generally treated as almost synonymous with ‘talking to the lobby’. This is partly why so much punditry is ‘narrative from noise’.

With no election for years and huge changes in the digital world, there is a chance and a need to do things very differently.

We’re particularly interested in deep experts on TV and digital. We also are interested in people who have worked in movies or on advertising campaigns. There are some very interesting possibilities in the intersection of technology and story telling — if you’ve done something weird, this may be the place for you.

I noticed in the recent campaign that the world of digital advertising has changed very fast since I was last involved in 2016. This is partly why so many journalists wrongly looked at things like Corbyn’s Facebook stats and thought Labour was doing better than us — the ecosystem evolves rapidly while political journalists are still behind the 2016 tech, hence why so many fell for Carole’s conspiracy theories. The digital people involved in the last campaign really knew what they are doing, which is incredibly rare in this world of charlatans and clients who don’t know what they should be buying. If you are interested in being right at the very edge of this field, join.

We have some extremely able people but we also must upgrade skills across the spad network.

G. Policy experts

One of the problems with the civil service is the way in which people are shuffled such that they either do not acquire expertise or they are moved out of areas they really know to do something else. One Friday, X is in charge of special needs education, the next week X is in charge of budgets.

There are, of course, general skills. Managing a large organisation involves some general skills. Whether it is Coca Cola or Apple, some things are very similar — how to deal with people, how to build great teams and so on. Experience is often over-rated. When Warren Buffett needed someone to turn around his insurance business he did not hire someone with experience in insurance: ‘When Ajit entered Berkshire’s office on a Saturday in 1986, he did not have a day’s experience in the insurance business’ (Buffett).

Shuffling some people who are expected to be general managers is a natural thing but it is clear Whitehall does this too much while also not training general management skills properly. There are not enough people with deep expertise in specific fields.

If you want to work in the policy unit or a department and you really know your subject so that you could confidently argue about it with world-class experts, get in touch.

It’s also the case that wherever you are most of the best people are inevitably somewhere else. This means that governments must be much better at tapping distributed expertise. Of the top 20 people in the world who best understand the science of climate change and could advise us what to do with COP 2020, how many now work as a civil servant/spad or will become one in the next 5 years?

G. Super-talented weirdos

People in SW1 talk a lot about ‘diversity’ but they rarely mean ‘true cognitive diversity’. They are usually babbling about ‘gender identity diversity blah blah’. What SW1 needs is not more drivel about ‘identity’ and ‘diversity’ from Oxbridge humanities graduates but more genuine cognitive diversity.

We need some true wild cards, artists, people who never went to university and fought their way out of an appalling hell hole, weirdos from William Gibson novels like that girl hired by Bigend as a brand ‘diviner’ who feels sick at the sight of Tommy Hilfiger or that Chinese-Cuban free runner from a crime family hired by the KGB. If you want to figure out what characters around Putin might do, or how international criminal gangs might exploit holes in our border security, you don’t want more Oxbridge English graduates who chat about Lacan at dinner parties with TV producers and spread fake news about fake news.

By definition I don’t really know what I’m looking for but I want people around No10 to be on the lookout for such people.

We need to figure out how to use such people better without asking them to conform to the horrors of ‘Human Resources’ (which also obviously need a bonfire).

*

Send a max 1 page letter plus CV to ideasfornumber10@gmail.com and put in the subject line ‘job/’ and add after the / one of: data, developer, econ, comms, projects, research, policy, misfit.

I’ll have to spend time helping you so don’t apply unless you can commit to at least 2 years.

I’ll bin you within weeks if you don’t fit — don’t complain later because I made it clear now.

I will try to answer as many as possible but last time I publicly asked for job applications in 2015 I was swamped and could not, so I can’t promise an answer. If you think I’ve insanely ignored you, persist for a while.

I will use this blog to throw out ideas. It’s important when dealing with large organisations to dart around at different levels, not be stuck with formal hierarchies. It will seem chaotic and ‘not proper No10 process’ to some. But the point of this government is to do things differently and better and this always looks messy. We do not care about trying to ‘control the narrative’ and all that New Labour junk and this government will not be run by ‘comms grid’.

As Paul Graham and Peter Thiel say, most ideas that seem bad are bad but great ideas also seem at first like bad ideas — otherwise someone would have already done them. Incentives and culture push people in normal government systems away from encouraging ‘ideas that seem bad’. Part of the point of a small, odd No10 team is to find and exploit, without worrying about media noise, what Andy Grove called ‘very high leverage ideas’ and these will almost inevitably seem bad to most.

I will post some random things over the next few weeks and see what bounces back — it is all upside, there’s no downside if you don’t mind a bit of noise and it’s a fast cheap way to find good ideas…