‘People, ideas, machines — in that order!’ Colonel Boyd

‘[R]ational systems exhibit universal drives towards self-protection, resource acquisition, replication and efficiency. Those drives will lead to anti-social and dangerous behaviour if not explicitly countered. The current computing infrastructure would be very vulnerable to unconstrained systems with these drives.’ Omohundro.

‘For progress there is no cure…’ von Neumann

This blog sketches a few recent developments connecting AI and issues around ‘systems management’ and government procurement.

The biggest problem for governments with new technologies is that the limiting factor on applying new technologies is not the technology but management and operational ideas which are extremely hard to change fast. This has been proved repeatedly: eg. the tank in the 1920s-30s or the development of ‘precision strike’ in the 1970s. These problems are directly relevant to the application of AI by militaries and intelligence services. The Pentagon’s recent crash program, Project Maven, discussed below, was an attempt to grapple with these issues.

‘The good news is that Project Maven has delivered a game-changing AI capability… The bad news is that Project Maven’s success is clear proof that existing AI technology is ready to revolutionize many national security missions… The project’s success was enabled by its organizational structure.‘

This blog sketches some connections between:

- Project Maven.

- The example of ‘precision strike’ in the 1970s, Marshal Ogarkov and Andy Marshall, implications for now — ‘anti-access / area denial’ (A2/AD), ‘Air-Sea Battle’ etc.

- Development of ‘precision strike’ to lethal autonomous cheap drone swarms hunting humans cowering underground.

- Adding AI to already broken nuclear systems and doctrines, hacking the NSA etc — mix coke, Milla Jovovich and some alpha engineers and you get…?

- A few thoughts on ‘systems management’ and procurement, lessons from the Manhattan Project etc.

- The Chinese attitude to ‘systems management’ and Qian Xuesen, combined with AI, mass surveillance, ‘social credit’ etc.

- A few recent miscellaneous episodes such as an interesting DARPA demo on ‘self-aware’ robots.

- Charts on Moore’s Law: what scale would a ‘Manhattan Project for AGI’ be?

- AGI safety — the alignment problem, the dangers of science as a ‘blind search algorithm’, closed vs open security architectures etc.

A theme of this blog since before the referendum campaign has been that thinking about organisational structure/dynamics can bring what Warren Buffett calls ‘lollapalooza’ results. What seems to be very esoteric and disconnected from ‘practical politics’ (studying things like the management of the Manhattan Project and Apollo) turns out to be extraordinarily practical (gives you models for creating super-productive processes).

Part of the reason lollapalooza results are possible is that almost nobody near the apex of power believes the paragraph above is true and they actively fight to stop people learning from extreme successes so there is gold lying on the ground waiting to be picked up for trivial costs. Nudging reality down an alternative branch of history in summer 2016 only cost ~£106 so the ‘return on investment’ if you think about altered GDP, technology, hundreds of millions of lives over decades and so on was truly lollapalooza. Politics is not like the stock market where you need to be an extreme outlier like Buffett/Munger to find such inefficiencies and results consistently. The stock market is an exploitable market where being right means you get rich and you help the overall system error-correct which makes it harder to be right (the mechanism pushes prices close to random, they’re not quite random but few can exploit the non-randomness). Politics/government is not like this. Billionaires who want to influence politics could get better ‘returns on investment’ than from early stage Amazon.

This blog is not directly about Brexit at all but if you are thinking — how could we escape this nightmare and turn government institutions from hopeless to high performance and what should we focus on to replace the vision of ‘influencing the EU’ that has been blown up by Brexit? — it will be of interest. Lessons that have been lying around for over half a century could have pushed the Brexit negotiations in a completely different direction and still could do but require an extremely different ‘model of effective action’ to dominant models in Westminster.

*

Project Maven: new organisational approaches for rapid deployment of AI to war / hybrid-war

The quotes below are from a piece in The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists about a recent AI project by the Pentagon. The most interesting aspect is not the technical details but the management approach and implications for Pentagon-style bureaucraties.

‘Project Maven is a crash Defense Department program that was designed to deliver AI technologies … to an active combat theater within six months from when the project received funding… Technologies developed through Project Maven have already been successfully deployed in the fight against ISIS. Despite their rapid development and deployment, these technologies are getting strong praise from their military intelligence users. For the US national security community, Project Maven’s frankly incredible success foreshadows enormous opportunities ahead — as well as enormous organizational, ethical, and strategic challenges.

‘In late April, Robert Work — then the deputy secretary of the Defense Department — wrote a memo establishing the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team, also known as Project Maven. The team had only six members to start with, but its small size belied the significance of its charter… Project Maven is the first time the Defense Department has sought to deploy deep learning and neural networks, at the level of state-of-the-art commercial AI, in department operations in a combat theater…

‘Every day, US spy planes and satellites collect more raw data than the Defense Department could analyze even if its whole workforce spent their entire lives on it. As its AI beachhead, the department chose Project Maven, which focuses on analysis of full-motion video data from tactical aerial drone platforms… These drone platforms and their full-motion video sensors play a major role in the conflict against ISIS across the globe. The tactical and medium-altitude video sensors of the Scan Eagle, MQ-1C, and MQ-9 produce imagery that more or less resembles what you see on Google Earth. A single drone with these sensors produces many terabytes of data every day. Before AI was incorporated into analysis of this data, it took a team of analysts working 24 hours a day to exploit only a fraction of one drone’s sensor data.

‘The Defense Department spent tens of billions of dollars developing and fielding these sensors and platforms, and the capabilities they offer are remarkable. Whenever a roadside bomb detonates in Iraq, the analysts can simply rewind the video feed to watch who planted it there, when they planted it, where they came from, and where they went. Unfortunately, most of the imagery analysis involves tedious work—people look at screens to count cars, individuals, or activities, and then type their counts into a PowerPoint presentation or Excel spreadsheet. Worse, most of the sensor data just disappears — it’s never looked at — even though the department has been hiring analysts as fast as it can for years… Plenty of higher-value analysis work will be available for these service members and contractors once low-level counting activity is fully automated.

‘The six founding members of Project Maven, though they were assigned to run an AI project, were not experts in AI or even computer science. Rather, their first task was building partnerships, both with AI experts in industry and academia and with the Defense Department’s communities of drone sensor analysts… AI experts and organizations who are interested in helping the US national security mission often find that the department’s contracting procedures are so slow, costly, and painful that they just don’t want to bother. Project Maven’s team — with the help of Defense Information Unit Experimental, an organization set up to accelerate the department’s adoption of commercial technologies — managed to attract the support of some of the top talent in the AI field (the vast majority of which lies outside the traditional defense contracting base). Figuring out how to effectively engage the tech sector on a project basis is itself a remarkable achievement…

‘Before Maven, nobody in the department had a clue how to properly buy, field, and implement AI. A traditional defense acquisition process lasts multiple years, with separate organizations defining the functions that acquisitions must perform, or handling technology development, production, or operational deployment. Each of these organizations must complete its activities before results are handed off to the next organization. When it comes to digital technologies, this approach often results in systems that perform poorly and are obsolete even before they are fielded.

‘Project Maven has taken a different approach, one modeled after project management techniques in the commercial tech sector: Product prototypes and underlying infrastructure are developed iteratively, and tested by the user community on an ongoing basis. Developers can tailor their solutions to end-user needs, and end users can prepare their organizations to make rapid and effective use of AI capabilities. Key activities in AI system development — labeling data, developing AI-computational infrastructure, developing and integrating neural net algorithms, and receiving user feedback — are all run iteratively and in parallel…

‘In Maven’s case, humans had to individually label more than 150,000 images in order to establish the first training data sets; the group hopes to have 1 million images in the training data set by the end of January. Such large training data sets are needed for ensuring robust performance across the huge diversity of possible operating conditions, including different altitudes, density of tracked objects, image resolution, view angles, and so on. Throughout the Defense Department, every AI successor to Project Maven will need a strategy for acquiring and labeling a large training data set…

‘From their users, Maven’s developers found out quickly when they were headed down the wrong track — and could correct course. Only this approach could have provided a high-quality, field-ready capability in the six months between the start of the project’s funding and the operational use of its output. In early December, just over six months from the start of the project, Maven’s first algorithms were fielded to defense intelligence analysts to support real drone missions in the fight against ISIS.

‘The good news is that Project Maven has delivered a game-changing AI capability… The bad news is that Project Maven’s success is clear proof that existing AI technology is ready to revolutionize many national security missions…

‘The project’s success was enabled by its organizational structure: a small, operationally focused, cross-functional team that was empowered to develop external partnerships, leverage existing infrastructure and platforms, and engage with user communities iteratively during development. AI needs to be woven throughout the fabric of the Defense Department, and many existing department institutions will have to adopt project management structures similar to Maven’s if they are to run effective AI acquisition programs. Moreover, the department must develop concepts of operations to effectively use AI capabilities—and train its military officers and warfighters in effective use of these capabilities…

‘Already the satellite imagery analysis community is working on its own version of Project Maven. Next up will be migrating drone imagery analysis beyond the campaign to defeat ISIS and into other segments of the Defense Department that use drone imagery platforms. After that, Project Maven copycats will likely be established for other types of sensor platforms and intelligence data, including analysis of radar, signals intelligence, and even digital document analysis… In October 2016, Michael Rogers (head of both the agency and US Cyber Command) said “Artificial Intelligence and machine learning … [are] foundational to the future of cybersecurity. … It is not the if, it’s only the when to me.”

‘The US national security community is right to pursue greater utilization of AI capabilities. The global security landscape — in which both Russia and China are racing to adapt AI for espionage and warfare — essentially demands this. Both Robert Work and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt have said that leadership in AI technology is critical to the future of economic and military power and that continued US leadership is far from guaranteed. Still, the Defense Department must explore this new technological landscape with a clear understanding of the risks involved…

‘The stakes are relatively low when AI is merely counting the number of cars filmed by a drone camera, but drone surveillance data can also be used to determine whether an individual is directly engaging in hostilities and is thereby potentially subject to direct attack. As AI systems become more capable and are deployed across more applications, they will engender ever more difficult ethical and legal dilemmas.

‘US military and intelligence agencies will have to develop effective technological and organizational safeguards to ensure that Washington’s military use of AI is consistent with national values. They will have to do so in a way that retains the trust of elected officials, the American people, and Washington’s allies. The arms-race aspect of artificial intelligence certainly doesn’t make this task any easier…

‘The Defense Department must develop and field AI systems that are reliably safe when the stakes are life and death — and when adversaries are constantly seeking to find or create vulnerabilities in these systems.

‘Moreover, the department must develop a national security strategy that focuses on establishing US advantages even though, in the current global security environment, the ability to implement advanced AI algorithms diffuses quickly. When the department and its contractors developed stealth and precision-guided weapons technology in the 1970s, they laid the foundation for a monopoly, nearly four decades long, on technologies that essentially guaranteed victory in any non-nuclear war. By contrast, today’s best AI tech comes from commercial and academic communities that make much of their research freely available online. In any event, these communities are far removed from the Defense Department’s traditional technology circles. For now at least, the best AI research is still emerging from the United States and allied countries, but China’s national AI strategy, released in July, poses a credible challenge to US technology leadership.’

Full article here: https://thebulletin.org/project-maven-brings-ai-fight-against-isis11374

Project Maven shows recurring lessons from history. Speed and adaptability are crucial to success in conflict and can be helped by new technologies. So is the capacity for new operational ideas about using new technologies. These ideas depend on unusual people. Bureaucracies naturally slow things down (for some good but mostly bad reasons), crush new ideas, and exclude unusual people in order to defend established interests. The limiting factor for the Pentagon in deploying advanced technology to conflict in a useful time period was not new technical ideas — overcoming its own bureaucracy was harder than overcoming enemy action. This is absolutely normal in conflict (e.g it was true of the 2016 referendum where dealing with internal problems was at least an order of magnitude harder and more costly than dealing with Cameron).

As Colonel Boyd used to shout to military audiences, ‘People, ideas, machines — in that order!’

*

DARPA, ‘precision strike’, the ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ and bureaucracies

The Project Maven experience is similar to the famous example of the tank. Everybody could see tanks were possible from the end of World War I but over 20 years Britain and France were hampered by their own bureaucracies in thinking about the operational implications and how to use them most effectively. Some in Britain and France did point out the possibilities but the possibilities were not absorbed into official planning. Powerful bureaucratic interests reinforced the normal sort of blindness to new possibilities. Innovative thinking flourished, relatively, in Germany where people like Guderian and von Manstein could see the possibilities for a very big increase in speed turning into a huge nonlinear advantage — possibilities applied to the ‘von Manstein plan’ that shocked the world in 1940. This was partly because the destruction of German forces after 1918 meant everything had to be built from scratch and this connects to another lesson about successful innovation: in the military, as in business, it is more likely if a new entity is given the job, as with the Manhattan Project to develop nuclear weapons. The consequences were devastating for the world in 1940 but, lucky for us, the nature of the Nazi regime meant that it made very similar errors itself, e.g regarding the importance of air power in general and long range bombers in particular. (This history is obviously very complex but this crude summary is roughly right about the main point)

There was a similar story with the technological developments mainly sparked by DARPA in the 1970s including stealth (developed in a classified program by the legendary ‘Skunk Works’, tested at ‘Area 51’), global positioning system (GPS), ‘precision strike’ long-range conventional weapons, drones, advanced wide-area sensors, computerised command and control (C2), and new intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities (ISR). The hope was that together these capabilities could automate the location and destruction of long-range targets and greatly improve simultaneously the precision, destructiveness, and speed of operations.

The approach became known in America as ‘deep-strike architectures’ (DSA) and in the Soviet Union as ‘reconnaissance-strike complexes’ (RUK). The Soviet Marshal Ogarkov realised that these developments, based on America’s superior ability to develop micro-electronics and computers, constituted what he called a ‘Military-Technical Revolution’ (MTR) and was an existential threat to the Soviet Union. He wrote about them from the late 1970s. (The KGB successfully stole much of the technology but the Soviet system still could not compete.) His writings were analysed in America particularly by Andy Marshall at the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment (ONA) and others. ONA’s analyses of what they started calling the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) in turn affected Pentagon decisions. In 1991 the Gulf War demonstrated some of these technologies just as the Soviet Union was imploding. In 1992 the ONA wrote a very influential report (The Military-Technical Revolution) which, unusually, they made public (almost all ONA documents remain classified).

The ~1978 Assault Breaker concept

Soviet depiction of Assault Breaker (Sergeyev, ‘Reconnaissance-Strike Complexes,’ Red Star, 1985)

In many ways Marshal Ogarkov thought more deeply about how to develop the Pentagon’s own technologies than the Pentagon did, hampered by the normal problems that the operationalising of new ideas threatened established bureaucratic interests, including the Pentagon’s procurement system. These problems have continued. It is hard to overstate the scale of waste and corruption in the Pentagon’s horrific procurement system (see below).

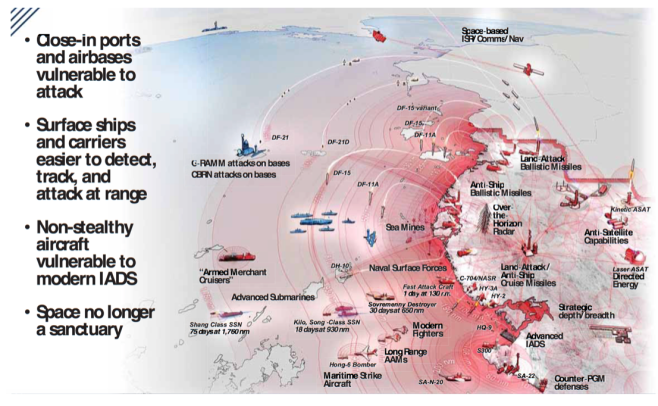

China has studied this episode intensely. It has integrated lessons into their ‘anti-access / area denial’ (A2/AD) efforts to limit American power projection in East Asia. America’s response to A2/AD is the ‘Air-Sea Battle’ concept. As Marshal Ogarkov predicted in the 1970s the ‘revolution’ has evolved into opposing ‘reconnaissance-strike complexes’ facing each other with each side striving to deploy near-nuclear force using extremely precise conventional weapons from far away, all increasingly complicated by possibilities for cyberwar to destroy the infrastructure on which all this depends and information operations to alter the enemy population’s perception (very Sun Tzu!).

Graphic: Operational risks of conventional US approach vs A2/AD (CSBA, 2016)

The penetration of the CIA by the KGB, the failure of the CIA to provide good predictions, the general American failure to understand the Soviet economy, doctrine and so on despite many billions spent over decades, the attempts by the Office of Net Assessment to correct institutional failings, the bureaucratic rivalries and so on — all this is a fascinating subject and one can see why China studies it so closely.

*

From experimental drones in the 1970s to drone swarms deployed via iPhone

The next step for reconnaissance-strike is the application of advanced robotics and artificial intelligence which could bring further order(s) of magnitude performance improvements, cost reductions, and increases in tempo. This is central to the US-China military contest. It will also affect everyone else as much of the technology becomes available to Third World states and small terrorist groups.

I wrote in 2004 about the farce of the UK aircraft carrier procurement story (and many others have warned similarly). Regardless of elections, the farce has continued to squander billions of pounds, enriching some of the worst corporate looters and corrupting public life via the revolving door of officials/lobbyists. Scrutiny by our MPs has been contemptible. They have built platforms that already cannot be sent to a serious war against a serious enemy. A teenager will be able to deploy a drone from their smartphone to sink one of these multi-billion dollar platforms. Such a teenager could already take out the stage of a Downing Street photo op with a little imagination and initiative, as I wrote about years ago

The drone industry is no longer dependent on its DARPA roots and is no longer tied to the economics of the Pentagon’s research budgets and procurement timetables. It is driven by the economics of the extremely rapidly developing smartphone market including Moore’s Law, plummeting costs for sensors and so on. Further, there are great advantages of autonomy including avoiding jamming counter-measures. Kalashnikov has just unveiled its drone version of the AK-47: a cheap anonymous suicide drone that flies to the target and blows itself up — it’s so cheap you don’t care. So you have a combination of exponentially increasing capabilities, exponentially falling costs, greater reliability, greater lethality, greater autonomy, and anonymity (if you’re careful and buy them through cut-outs etc). Then with a bit of added sophistication you add AI face recognition etc. Then you add an increasing capacity to organise many of these units at scale in a swarm, all running off your iPhone — and consider how effective swarming tactics were for people like Alexander the Great.

This is why one of the world’s leading AI researchers, Stuart Russell (professor of computer science at Berkeley) has made this warning:

‘The capabilities of autonomous weapons will be limited more by the laws of physics — for example, by constraints on range, speed and payload — than by any deficiencies in the AI systems that control them. For instance, as flying robots become smaller, their manoeuvrability increases and their ability to be targeted decreases… Despite the limits imposed by physics, one can expect platforms deployed in the millions, the agility and lethality of which will leave humans utterly defenceless…

‘A very, very small quadcopter, one inch in diameter can carry a one- or two-gram shaped charge. You can order them from a drone manufacturer in China. You can program the code to say: “Here are thousands of photographs of the kinds of things I want to target.” A one-gram shaped charge can punch a hole in nine millimeters of steel, so presumably you can also punch a hole in someone’s head. You can fit about three million of those in a semi-tractor-trailer. You can drive up I-95 with three trucks and have 10 million weapons attacking New York City. They don’t have to be very effective, only 5 or 10% of them have to find the target.

‘There will be manufacturers producing millions of these weapons that people will be able to buy just like you can buy guns now, except millions of guns don’t matter unless you have a million soldiers. You need only three guys to write the program and launch them. So you can just imagine that in many parts of the world humans will be hunted. They will be cowering underground in shelters and devising techniques so that they don’t get detected. This is the ever-present cloud of lethal autonomous weapons… There are really no technological breakthroughs that are required. Every one of the component technologies is available in some form commercially… It’s really a matter of just how much resources are invested in it.’

There is some talk in London of ‘what if there is an AI arms race’ but there is already an AI/automation arms race between companies and between countries — it’s just that Europe is barely relevant to the cutting edge of it. Europe wants to be a world player but it has totally failed to generate anything approaching what is happening in coastal America and China. Brussels spends its time on posturing, publishing documents about ‘AI and trust’, whining, spreading fake news about fake news (while ignoring experts like Duncan Watts), trying to damage Silicon Valley companies rather than considering how to nourish European entities with real capabilities, and imposing bad regulation like GDPR (that ironically was intended to harm Google/Facebook but actually helped them in some ways because Brussels doesn’t understand them).

Britain had a valuable asset, Deep Mind, and let Google buy it for trivial money without the powers-that-be in Whitehall understanding its significance — it is relevant but it is not under British control. Britain has other valuable assets — for example, it is a potential strategic asset to have the AI centre, financial centre, and political centre all in London, IF politicians cared and wanted to nourish AI research and companies. Very obviously, right now we have a MP/official class that is unfit to do this even if they had the vaguest idea what to do, which almost none do (there is a flash of hope on genomics/AI).

Unlike during the Cold War when the Soviet Union could not compete in critical industries such as semi-conductors and consumer electronics, China can compete, is competing, and in some areas is already ahead.

The automation arms race is already hitting all sorts of low skilled jobs from baristas to factory cleaning, some of which will be largely eliminated much more quickly than economists and politicians expect. Many agricultural jobs are being rapidly eliminated as are jobs in fields like mining and drilling. Look at a modern mine and you will see driverless trucks on the ground and drones overhead. The implications for millions who make a living from driving is now well known. (This also has obvious implications for the wisdom of allowing millions of un-skilled immigrants and one of the oddities of Silicon Valley is that people there simultaneously argue a) politicians are clueless about the impact of automation on unskilled people and b) politicians should allow millions more unskilled immigrants into the country — an example of how technical people are not always as rational about politics as they think they are.)

This automation arms race will affect different countries at different speeds depending on their exposure to fields that are ripe for disruption sooner or later. If countries cannot tax those companies that lead in AI, they will have narrower options. They may even be forced into a sort of colony status. Those who think this is an exaggeration should look at China’s recent deals in Africa where countries are handing over vast amounts of data to China on extremely unfavourable terms. Huge server farms in China are processing facial recognition data on millions of Africans who have no idea their personal data has been handed over. The western media focuses on Facebook with almost no coverage of these issues.

In the extreme case, a significant lead in AI for country X could lead to a self-reinforcing cycle in which it increasingly dominates economically, scientifically, and militarily and perhaps cannot be caught as Ian Hogarth has argued and to which Putin recently alluded.

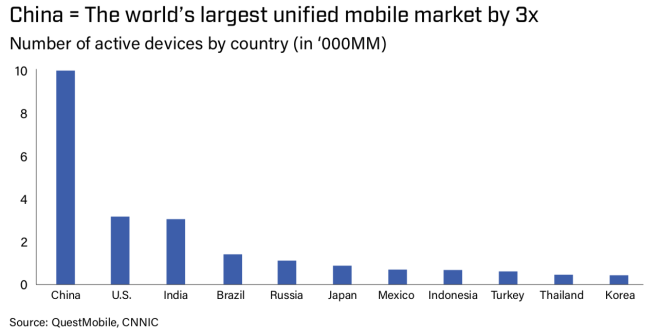

China’s investment in AI — more data = better product = more users = more revenue = better talent + more data in a beautiful flywheel…

China has about x3 number of internet users than America but the gap in internet and mobile usage is much larger. ‘In China, people use their mobile phones to pay for goods 50 times more often than Americans. Food delivery volume in China is 10 times more than that of the United States. And shared bicycle usage is 300 times that of the US. This proliferation of data — with more people generating far more information than any other country – is the fuel for improving China’s AI’ (report).

China’s AI policy priority is clear. The ‘Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan‘ announced in July 2017 states that China should catch America by 2020 and be the global leader by 2030. Xi Jinping emphasises this repeatedly.

*

Some implications for entangling AI with WMD — take a Milla Jovovich lookalike then add some alpha engineers…

It is important to consider nuclear safety when thinking about AI safety.

The missile silos for US nuclear weapons have repeatedly been shown to be terrifyingly insecure. Sometimes incidents are just bog standard unchecked incompetence: e.g nuclear weapons are accidentally loaded onto a plane which is then left unattended on an insecure airfield. Coke, great unconventional hookers and a bit of imagination get you into nuclear facilities, just as they get you into pretty much anywhere.

Cyber security is also awful. For example, in a major 2013 study the Pentagon’s Defense Science Board concluded that the military’s systems were vulnerable to cyberattacks, the government was ‘not prepared to defend against this threat’, and a successful cyberattack could cause military commanders to lose ‘trust in the information and ability to control U.S. systems and forces [including nuclear]’ (cf. this report). Since then, the NSA itself has had its deepest secrets hacked by an unidentified actor (possibly/probably AI-enabled) in a breach much more serious but infinitely less famous than Snowden (and resembles a chapter in the best recent techno-thriller, Daemon).

This matches research just published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists on the most secure (Level 3/enhanced and Level 4) bio-labs. It is now clear that laboratories conducting research on viruses that could cause a global pandemic are extremely dangerous. I am not aware of any mainstream media in Britain reporting this (story here).

Further, the systems for coping with nuclear crises have failed repeatedly. They are extremely vulnerable to false alarms, malicious attacks or even freaks like, famously, a bear (yes, a bear) triggering false alarms. We have repeatedly escaped accidental nuclear war because of flukes such as odd individuals not passing on ‘launch’ warnings or simply refusing to act. The US National Security Adviser has sat at the end of his bed looking at his sleeping wife ‘knowing’ she won’t wake up while pondering his advice to the President on a counterattack that will destroy half the world, only to be told minutes later the launch warning was the product of a catastrophic error. These problems have not been dealt with. We don’t know how bad this problem is: many details are classified and many incidents are totally unreported.

Further, the end of the Cold War gave many politicians and policy people in the West the completely false idea that established ideas about deterrence had been vindicated but they have not been vindicated (cf. Payne’s Fallacies of Cold War deterrence and The Great American Gamble). Senior decision-makers are confident that their very dangerous ideas are ‘rational’.

US and Russian nukes remain on ‘launch on warning’ — i.e a hair trigger — so the vulnerabilities could recur any time. Threats to use them are explicitly contemplated over crises such as Taiwan and Kashmir. Nuclear weapons have proliferated and are very likely to proliferate further. There are now thousands of people, including North Korean and Pakistani scientists, who understand the technology. And there is a large network of scientists involved in the classified Soviet bio-weapon programme that was largely unknown to western intelligence services before the end of the Cold War and has dispersed across the world.

These are all dangers already known to experts. But now we are throwing at these wobbling systems and flawed/overconfident thinking the development of AI/ML capabilities. This will exacerbate all these problems and make crises even faster, more confusing and more dangerous.

Yes, you’re right to ask ‘why don’t I read about this stuff in the mainstream media?’. There is very little media coverage of reports on things like nuclear safety and pretty much nobody with real power pays any attention to all this. If those at the apex of power don’t take nuclear safety seriously, why would you think they are on top of anything? Markets and science have done wondrous things but they cannot by themselves fix such crazy incentive problems with government institutions.

*

Government procurement — ‘the horror, the horror’

The problem of ‘rational procurement’ is incredibly hard to solve and even during existential conflicts problems with incentives recur. If state agencies, out of fear of what opponents might be doing, create organisations that escape most normal bureaucratic constraints, then AI will escalate in importance to the military and intelligence services even more rapidly than it already is. It is possible that China will build organisations to deploy AI to war/pseudo-war/hybrid-war faster and better than America.

In January 2017 I wrote about systems engineering and systems management — an approach for delivering extremely complex and technically challenging projects. (It was already clear the Brexit negotiations were botched, that Heywood, Hammond et al had effectively destroyed any sort of serious negotiating position, and I suggested Westminster/Whitehall had to learn from successful management of complex projects to avert what would otherwise be a debacle.) These ideas were born with the Manhattan Project to build the first nuclear bomb, the ICBMs project in the 1950s, and the Apollo program in the 1960s which put man on the moon. These projects combined a) some of the most astonishing intellects the world has seen of which a subset were also brilliant at navigating government (e.g von Neumann) and b) phenomenally successful practical managers: e.g General Groves on Manhattan Project, Bernard Schriever on ICBMs and George Mueller on Apollo.

The story we are told about the Manhattan Project focuses almost exclusively on the extraordinary collection of physicists and mathematicians at Los Alamos but they were a relatively small part of the whole story which involved an engineer building an unprecedented operation at multiple sites across America in secret and with extraordinary speed while many doubted the project was possible — then coordinating multiple projects, integrating distributed expertise and delivering a functioning bomb.

If you read Groves’ fascinating book, Now It Can Be Told, and read a recent biography of him, in many important ways you will acquire what is effectively cutting-edge knowledge today about making huge endeavours work — ‘cutting-edge’ because almost nobody has learned from this (see below). If you are one of the many MPs aspiring to be not just Prime Minister but a Prime Minister who gets important things done, there are very few books that would repay careful study as much as Groves’. If you do then you could avoid joining the list of Major, Blair, Brown, Cameron and May who bungle around for a few years before being spat out to write very similar accounts about how they struggled to ‘find the levers of power’, couldn’t get officials to do what they want, and never understood how to get things done.

Systems management is generally relevant to the question: how best to manage very big complex projects? It was relevant to the referendum (Victoria Woodcock was Vote Leave’s George Mueller). It is relevant to the Brexit negotiations and the appalling management process between May/Hammond/Heywood/Robbins et al, which has been a case study in how not to manage a complex project (Parliament also deserves much blame for never scrutinising this process). It is relevant to China’s internal development and the US-China geopolitical struggle. It is relevant to questions like ‘how to avoid nuclear war’ and ‘how would you build a Manhattan Project for safe AGI?’. It is relevant to how you could develop a high performance team in Downing Street that could end the current farce. The same issues and lessons crop up in every account of a Presidency and the role of the Chief of Staff. If you want to change Whitehall from 1) ‘failure is normal’ to 2) ‘align incentives with predictive accuracy, operational excellence and high performance’, then systems management provides an extremely valuable anti-checklist for Whitehall.

Given vital principles were established more than half a century ago that were proved to do things much faster and more effectively than usual, it would be natural to assume that these lessons became integrated in training and practice both in the worlds of management and politics/government. This did not happen. In fact, these lessons have been ‘unlearned’.

General Groves was pushed out of the Pentagon (‘too difficult’). The ICBM project, conducted in extreme panic post-Sputnik, had to re-create an organisation outside the Pentagon and re-learn Groves’ lessons a decade later. NASA was a mess until Mueller took over and imported the lessons from Manhattan and ICBMs. After Apollo’s success in 1969, Mueller left and NASA reverted to being a ‘normal’ organisation and forgot his successful approach. (The plans Mueller left for developing a manned lunar base, space commercialisation, and man on Mars by the end of the 1980s were also tragically abandoned.)

While Mueller was putting man on the moon, MacNamara’s ‘Whizz Kids’ in the Pentagon, who took America into the Vietnam War, were dismantling the successful approach to systems management claiming that it was ‘wasteful’ and they could do it ‘more efficiently’. Their approach was a disaster and not just regarding Vietnam. The combination of certain definitions of ‘efficiency’ and new legal processes ensured that procurement was routinely over-budget, over-schedule, over-promising, and generated more and more scandals. Regardless of failure the MacNamara approach metastasised across the Pentagon. Incentives are so disastrously misaligned that almost every attempt at reform makes these problems worse and lawyers and lobbyists get richer. Of course, if lawmakers knew how the Manhattan Project and Apollo were done — the lack of ‘legal process’, things happening with a mere handshake instead of years of reviews enriching lawyers! — they would be stunned.

Successes since the 1960s have often been freaks (e.g the F-16, Boyd’s brainchild) or ‘black’ projects (e.g stealth) and often conducted in SkunkWorks-style operations outside normal laws. It is striking that US classified special forces, JSOC (equivalent to SAS/SBS etc), routinely use a special process to procure technologies outside the normal law to avoid the delays. This connects to George Mueller saying late in life that Apollo would be impossible with the current legal/procurement system and it could only be done as a ‘black’ program.

The lessons of success have been so widely ‘unlearned’ throughout the government system that when Obama tried to roll out ObamaCare, it blew up. When they investigated, the answer was: we didn’t use systems management so the parts didn’t connect and we never tested this properly. Remember: Obama had the support of the vast majority of Silicon Valley expertise but this did not avert disaster. All anyone had to do was read Groves’ book and call Sam Altman or Patrick Collison and they could have provided the expertise to do it properly but none of Obama’s staff or responsible officials did.

The UK is the same. MPs constantly repeat the absurd SW1 mantra that ‘there’s no money’ while handing out a quarter of a TRILLION pounds every year on procurement and contracting. I engaged with this many times in the Department for Education 2010-14. The Whitehall procurement system is embedded in the dominant framework of EU law (the EU law is bad but UK officials have made it worse). It is complex, slow and wasteful. It hugely favours large established companies with powerful political connections — true corporate looters. The likes of Carillion and lawyers love it because they gain from the complexity, delays, and waste. It is horrific for SMEs to navigate and few can afford even to try to participate. The officials in charge of multi-billion processes are mostly mediocre, often appalling. In the MoD corruption adds to the problems.

Because of mangled incentives and reinforcing culture, the senior civil service does not care about this and does not try to improve. Total failure is totally irrelevant to the senior civil service and is absolutely no reason to change behaviour even if it means thousands of people killed and many billions wasted. Occasionally incidents like Carillion blow up and the same stories are written and the same quotes given — ‘unbelievable’, ‘scandal’, ‘incompetence’, ‘heads will roll’. Nothing changes. The closed and dysfunctional Whitehall system fights to stay closed and dysfunctional. The media caravan soon rolls on. ‘Reform’ in response to botches and scandals almost inevitably makes things even slower and more expensive — even more focus on process rather than outcomes, with the real focus being ‘we can claim to have acted properly because of our Potemkin process’. Nobody is incentivised to care about high performance and error-correction. The MPs ignore it all. Select Committees issue press releases about ‘incompetence’ but never expose the likes of Heywood to persistent investigation to figure out what has really happened and why. Nobody cares.

This culture has been encouraged by the most senior leaders. The recent Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood assured us all that the civil service could easily cope with Brexit and the civil service would handle Brexit fine and ‘definitely on digital, project management we’ve got nothing to learn from the private sector’. His predecessor, O’Donnell, made similar asinine comments. The fact that Heywood could make such a laughable claim after years of presiding over expensive debacle after expensive debacle and be universally praised by Insiders tells you all you need to know about ‘the blind leading the blind’ in Westminster. Heywood was a brilliant courtier-fixer but he didn’t care about management and operational excellence. Whitehall now incentivises the promotion of courtier-fixers, not great managers like Groves and Mueller. Management, like science, is regarded contemptuously as something for the lower orders to think about, not the ‘strategists’ at the top.

Long-term leadership from the likes of O’Donnell and Heywood is why officials know that practically nobody is ever held accountable regardless of the scale of failure. Being in charge of massive screwups is no barrier to promotion. Operational excellence is no requirement for promotion. You will often see the official in charge of some debacle walking to the tube at 4pm (‘compressed hours’ old boy) while the debacle is live on TV (I know because I saw this regularly in the DfE). The senior civil service now operates like a protected caste to preserve its power and privileges regardless of who the ignorant plebs vote for.

You can see how crazy the incentives are when you consider elections. If you look back at recent British elections the difference in the spending plans between the two sides has been a tiny fraction of the £250 billion p/a procurement and contracting budget — yet nobody ever really talks about this budget, it is the great unmentionable subject in Westminster! There’s the odd slogan about ‘let’s cut waste’ but the public rightly ignores this and assumes both sides will do nothing about it out of a mix of ignorance, incompetence and flawed incentives so big powerful companies continue to loot the taxpayer. Look at both parties now just letting the HS2 debacle grow and grow with the budget out of control, the schedule out of control, officials briefing ludicrously that the ‘high speed’ rail will be SLOWED DOWN to reduce costs and so on, all while an army of privileged looters, lobbyists, and lawyers hoover up taxpayer cash.

And now, when Brexit means the entire legal basis for procurement is changing, do these MPs, ministers and officials finally examine it and see how they could improve? No of course not! The top priority for Heywood et al viz Brexit and procurement has been to get hapless ministers to lock Britain into the same nightmare system even after we leave the EU — nothing must disrupt the gravy train! There’s been a lot of talk about £350 million per week for the NHS since the referendum. I could find this in days and in ways that would have strong public support. But nobody is even trying to do this and if some minister took a serious interest, they would soon find all sorts of things going wrong for them until the PermSec has a quiet word and the natural order is restored…

To put the failures of politicians and official in context, it is fascinating that most of the commercial world also ignores the crucial lessons from Groves et al! Most commercial megaprojects are over-schedule, over-budget, and over-promise. The data shows that there has been little improvement over decades. (Cf. What You Should Know About Megaprojects, and Why, Flyvbjerg). And look at this 2019 article in Harvard Business Review which, remarkably, argues that managers in modern MBA programmes are taught NOT TO VALUE OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE! ‘Operational effectiveness — doing the same thing as other companies but doing it exceptionally well — is not a path to sustainable advantage in the competitive universe’, elite managers are taught. The authors have looked at a company data and concluded that, shock horror, operational excellence turns out to be vital after all! They conclude:

‘[T]he management community may have badly underestimated the benefits of core management practices [and] it’s unwise to teach future leaders that strategic decision making and basic management processes are unrelated.’ [!]

The study of management, like politics, is not a field with genuine expertise. Like other social sciences there is widespread ‘cargo cult science’, fads and charlatans drowning out core lessons. This makes it easier to understand the failure of politicians: when elite business schools now teach students NOT to value operational excellence, when supposed management gurus like MacNamara actually push things in a worse direction, then it is less surprising people like Cameron and Heywood don’t know know which way to turn. Imagine the normal politician or senior official in Washington or London. They have almost no exposure to genuinely brilliant managers or very well run organisations. Their exposure is overwhelmingly to ‘normal’ CEOs of public companies and normal bureaucracies. As the most successful investors in world history, Buffett and Munger, have pointed out for over 50 years, many of these corporate CEOs, the supposedly ‘serious people’, don’t know what they are doing and have terrible incentives.

But surely if someone recently created something unarguably massively world-changing, like inventing the internet and personal computing, then everyone would pay attention, right? WRONG! I wrote this (2018) about the extraordinary ARPA-PARC episode, which created much of the ecosystem for interactive personal computing and the internet and provided a model for how to conduct high-risk-high-payoff technology research.

There is almost no research funded on ARPA-PARC principles worldwide. ARPA was deliberately made less like what it was like when it created the internet. The man most responsible for PARC’s success, Robert Taylor, was fired and the most effective team in the history of computing research was disbanded. XEROX notoriously could not overcome its internal incentive problems and let Steve Jobs and Bill Gates develop the ideas. Although politicians love giving speeches about ‘innovation’ and launching projects for PR, governments subsequently almost completely ignored the lessons of how to create superproductive processes and there are almost zero examples of the ARPA-PARC approach in the world today (an interesting partial exception is Janelia). Whitehall, as a subset of its general vandalism towards science, has successfully resisted all attempts at learning from ARPA for decades and this has been helped by the attitude of leading scientists themselves whose incentives push them toward supporting objectively bad funding models. In science as well as politics, incentives can be destructive and stop learning. As Alan Kay, one of the crucial PARC researchers, wrote:

‘The most interesting thing has been the contrast between appreciation/exploitation of the inventions/contributions versus the almost complete lack of curiosity and interest in the processes that produced them… [I]n most processes today — and sadly in most important areas of technology research — the administrators seem to prefer to be completely in control of mediocre processes to being “out of control” with superproductive processes.They are trying to “avoid failure” rather than trying to “capture the heavens”.’’

Or as George Mueller said later in life about the institutional imperative and project failures:

‘Fascinating that the same problems recur time after time, in almost every program, and that the management of the program, whether it happened to be government or industry, continues to avoid reality.’

So, on one hand, radical improvements in non-military spheres would be a wonderful free lunch. We simply apply old lessons, scale them up with technology and there are massive savings for free.

But wouldn’t it be ironic if we don’t do this — instead, we keep our dysfunctional systems for non-military spheres and carry on the waste, failure and corruption but we channel the Cold War and, in the atmosphere of an arms race, America and China apply the lessons from Groves, Schreiver and Mueller but to military AI procurement?!

Not everybody has unlearned the lessons from Groves and Mueller…

*

China: a culture of learning from systems management

‘All stable processes we shall predict. All unstable processes we shall control.’ von Neumann.

In Science there was an interesting article on Qian Xuesen, the godfather of China’s nuclear and space programs which also had a profound affect on ideas about government. Qian studied in California at Caltech where he worked with the Hungarian mathematician Theodore von Kármán who co-founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) which worked on rockets after 1945.

‘In the West, systems engineering’s heyday has long passed. But in China, the discipline is deeply integrated into national planning. The city of Wuhan is preparing to host in August the International Conference on Control Science and Systems Engineering, which focuses on topics such as autonomous transportation and the “control analysis of social and human systems.” Systems engineers have had a hand in projects as diverse as hydropower dam construction and China’s social credit system, a vast effort aimed at using big data to track citizens’ behavior. Systems theory “doesn’t just solve natural sciences problems, social science problems, and engineering technology problems,” explains Xue Huifeng, director of the China Aerospace Laboratory of Social System Engineering (CALSSE) and president of the China Academy of Aerospace Systems Science and Engineering in Beijing. “It also solves governance problems.”

‘The field has resonated with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who in 2013 said that “comprehensively deepening reform is a complex systems engineering problem.” So important is the discipline to the Chinese Communist Party that cadres in its Central Party School in Beijing are required to study it. By applying systems engineering to challenges such as maintaining social stability, the Chinese government aims to “not just understand reality or predict reality, but to control reality,” says Rogier Creemers, a scholar of Chinese law at the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies in the Netherlands…

‘In a building flanked by military guards, systems scientists from CALSSE sit around a large conference table, explaining to Science the complex diagrams behind their studies on controlling systems. The researchers have helped model resource management and other processes in smart cities powered by artificial intelligence. Xue, who oversees a project named for Qian at CALSSE, traces his work back to the U.S.-educated scientist. “You should not forget your original starting point,” he says…

‘The Chinese government claims to have wired hundreds of cities with sensors that collect data on topics including city service usage and crime. At the opening ceremony of China’s 19th Party Congress last fall, Xi said smart cities were part of a “deep integration of the internet, big data, and artificial intelligence with the real economy.”… Xue and colleagues, for example, are working on how smart cities can manage water resources. In Guangdong province, the researchers are evaluating how to develop a standardized approach for monitoring water use that might be extended to other smart cities.

‘But Xue says that smart cities are as much about preserving societal stability as streamlining transportation flows and mitigating air pollution. Samantha Hoffman, a consultant with the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, says the program is tied to long-standing efforts to build a digital surveillance infrastructure and is “specifically there for social control reasons” (Science, 9 February, p. 628). The smart cities initiative builds on 1990s systems engineering projects — the “golden” projects — aimed at dividing cities into geographic grids for monitoring, she adds.

‘Layered onto the smart cities project is another systems engineering effort: China’s social credit system. In 2014, the country’s State Council outlined a plan to compile data on individuals, government officials, and companies into a nationwide tracking system by 2020. The goal is to shape behavior by using a mixture of carrots and sticks. In some citywide and commercial pilot projects already underway, individuals can be dinged for transgressions such as spreading rumors online. People who receive poor marks in the national system may eventually be barred from travel and denied access to social services, according to government documents…

‘Government documents refer to the social credit system as a “social systems engineering project.” Details about which systems engineers consulted on the project are scant. But one theory that may have proved useful is Qian’s “open complex giant system,” Zhu says. A quarter-century ago, Qian proposed that society is a system comprising millions of subsystems: individual persons, in human parlance. Maintaining control in such a system is challenging because people have diverse backgrounds, hold a broad spectrum of opinions, and communicate using a variety of media, he wrote in 1993 in the Journal of Systems Engineering and Electronics. His answer sounds like an early road map for the social credit system: to use then-embryonic tools such as artificial intelligence to collect and synthesize reams of data. According to published papers, China’s hard systems scientists also use approaches derived from Qian’s work to monitor public opinion and gauge crowd behavior…

‘Hard systems engineering worked well for rocket science, but not for more complex social problems, Gu says: “We realized we needed to change our approach.” He felt strongly that any methods used in China had to be grounded in Chinese culture.

‘The duo came up with what it called the WSR approach: It integrated wuli, an investigation of facts and future scenarios; shili, the mathematical and conceptual models used to organize systems; and renli. Though influenced by U.K. systems thinking, the approach was decidedly eastern, its precepts inspired by the emphasis on social relationships in Chinese culture. Instead of shunning mathematical approaches, WSR tried to integrate them with softer inquiries, such as taking stock of what groups a project would benefit or harm. WSR has since been used to calculate wait times for large events in China and to determine how China’s universities perform, among other projects…

‘Zhu … recently wrote that systems science in China is “under a rationalistic grip, with the ‘scientific’ leg long and the democratic leg short.” Zhu says he has no doubt that systems scientists can make projects such as the social credit system more effective. However, he cautions, “Systems approaches should not be just a convenient tool in the expert’s hands for realizing the party’s wills. They should be a powerful weapon in people’s hands for building a fair, just, prosperous society.”’

In Open Complex Giant System (1993), Qian Xuesen compares the study of physics, where large complex systems can be studied using the phenomenally successful tools of statistical mechanics, and the study of society which has no such methods. He describes an overall approach in which fields spanning physical sciences, study of the mind, medicine, geoscience and so on must be integrated in a sort of uber-field he calls ‘social systems engineering‘.

‘Studies and practices have clearly proved that the only feasible and effective way to treat an open complex giant system is a metasynthesis from the qualitative to the quantitative, i.e. the meta—synthetic engineering method. This method has been extracted, generalized and abstracted from practical studies…’

This involves integrating: scientific theories, data, quantitative models, qualitative practical expert experience into ‘models built from empirical data and reference material, with hundreds and thousands of parameters’ then simulated.

‘This is quantitative knowledge arising from qualitative understanding. Thus metasynthesis from qualitative to quantitative approach is to unite organically the expert group, data, all sorts of information, and the computer technology, and to unite scien- tific theory of various disciplines and human experience and knowledge.’

He gives some examples and gives this diagram as a high level summary:

So, China is combining:

- A massive ~$150 billion data science/AI investment program with the goal of global leadership in the science/technology and economic dominance.

- A massive investment program in associated science/technology such as quantum information/computing.

- A massive domestic surveillance program combining AI, facial recognition, genetic identification, the ‘social credit system’ and so on.

- A massive anti-access/area denial military program aimed at America/Taiwan.

- A massive technology espionage program that, for example, successfully stole the software codes for the F-35.

- A massive innovation ecosystem that rivals Silicon Valley and may eclipse it (cf. this fascinating documentary on Shenzhen).

- The use of proven systems management techniques for integrating principles of effective action to predict and manage complex systems at large scale.

America led the development of AI technologies and has the huge assets of its universities, a tradition (weakening) of welcoming scientists (since they opened Princeton to Einstein, von Neumann and Gödel in the 1930s), and the ecosystem of places like Silicon Valley.

It is plausible that China could find a way within 15 years to find some nonlinear asymmetries that provide an edge while, channeling Marshal Ogarkov, it outthinks the Pentagon in management and operations.

*

A few interesting recent straws in the AI/robotics wind

I blogged recently about Judea Pearl. He is one of the most important scholars in the field of causal reasoning. He wrote a short paper about the limits of state-of-the-art AI systems using ‘deep learning’ neural networks — such as the AlphaGo system which recently conquered the game of GO — and how these systems could be improved. Humans can interrogate stored representations of their environment with counter-factual questions: how to instantiate this in machines? (Also economists, NB. Pearl’s statement that ‘I can hardly name a handful (<6) of economists who can answer even one causal question posed in ucla.in/2mhxKdO‘.)

In an interview he said this about self-aware robots:

‘If a machine does not have a model of reality, you cannot expect the machine to behave intelligently in that reality. The first step, one that will take place in maybe 10 years, is that conceptual models of reality will be programmed by humans. The next step will be that machines will postulate such models on their own and will verify and refine them based on empirical evidence. That is what happened to science; we started with a geocentric model, with circles and epicycles, and ended up with a heliocentric model with its ellipses.

‘We’re going to have robots with free will, absolutely. We have to understand how to program them and what we gain out of it. For some reason, evolution has found this sensation of free will to be computationally desirable… Evidently, it serves some computational function.

‘I think the first evidence will be if robots start communicating with each other counterfactually, like “You should have done better.” If a team of robots playing soccer starts to communicate in this language, then we’ll know that they have a sensation of free will. “You should have passed me the ball — I was waiting for you and you didn’t!” “You should have” means you could have controlled whatever urges made you do what you did, and you didn’t.

[When will robots be evil?] When it appears that the robot follows the advice of some software components and not others, when the robot ignores the advice of other components that are maintaining norms of behavior that have been programmed into them or are expected to be there on the basis of past learning. And the robot stops following them.’

A DARPA project recently published this on self-aware robots.

‘A robot that learns what it is, from scratch, with zero prior knowledge of physics, geometry, or motor dynamics. Initially the robot does not know if it is a spider, a snake, an arm—it has no clue what its shape is. After a brief period of “babbling,” and within about a day of intensive computing, their robot creates a self-simulation. The robot can then use that self-simulator internally to contemplate and adapt to different situations, handling new tasks as well as detecting and repairing damage in its own body…

‘Initially, the robot moved randomly and collected approximately one thousand trajectories, each comprising one hundred points. The robot then used deep learning, a modern machine learning technique, to create a self-model. The first self-models were quite inaccurate, and the robot did not know what it was, or how its joints were connected. But after less than 35 hours of training, the self-model became consistent with the physical robot to within about four centimeters…

‘Lipson … notes that self-imaging is key to enabling robots to move away from the confinements of so-called “narrow-AI” towards more general abilities. “This is perhaps what a newborn child does in its crib, as it learns what it is,” he says. “We conjecture that this advantage may have also been the evolutionary origin of self-awareness in humans. While our robot’s ability to imagine itself is still crude compared to humans, we believe that this ability is on the path to machine self-awareness.”

‘Lipson believes that robotics and AI may offer a fresh window into the age-old puzzle of consciousness. “Philosophers, psychologists, and cognitive scientists have been pondering the nature self-awareness for millennia, but have made relatively little progress,” he observes. “We still cloak our lack of understanding with subjective terms like ‘canvas of reality,’ but robots now force us to translate these vague notions into concrete algorithms and mechanisms.”

‘Lipson and Kwiatkowski are aware of the ethical implications. “Self-awareness will lead to more resilient and adaptive systems, but also implies some loss of control,” they warn. “It’s a powerful technology, but it should be handled with care.”’

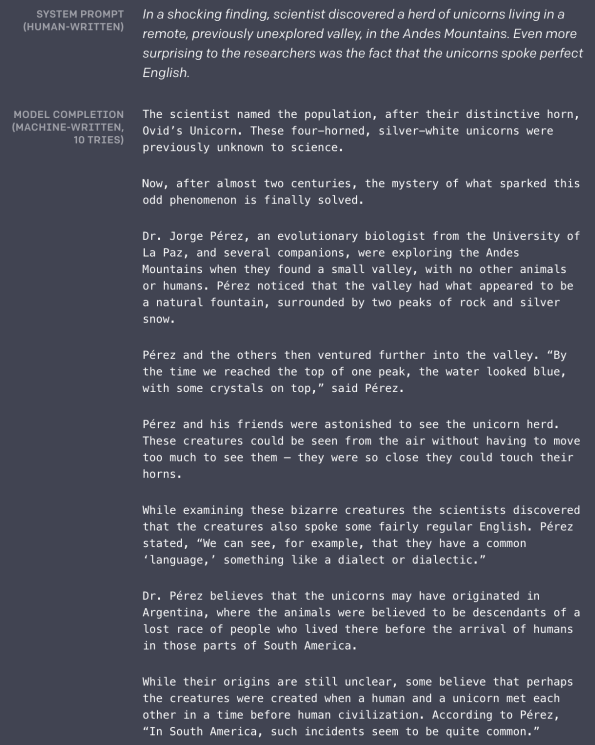

Recently, OpenAI, one of the world leaders in AI founded by Sam Altman and Elon Musk, announced:

‘… a large-scale unsupervised language model which generates coherent paragraphs of text, achieves state-of-the-art performance on many language modeling benchmarks, and performs rudimentary reading comprehension, machine translation, question answering, and summarization — all without task-specific training… The model is chameleon-like — it adapts to the style and content of the conditioning text. This allows the user to generate realistic and coherent continuations about a topic of their choosing… Our model is capable of generating samples from a variety of prompts that feel close to human quality and show coherence over a page or more of text… These samples have substantial policy implications: large language models are becoming increasingly easy to steer towards scalable, customized, coherent text generation, which in turn could be used in a number of beneficial as well as malicious ways.’ (bold added).

OpenAI has not released the full model yet because they take safety issues seriously. Cf. this for a discussion of some safety issues and links. As the author says re some of the complaints about OpenAI not releasing the full model, when you find normal cyber security flaws you do not publish the problem immediately — that is a ‘zero day attack’ and we should not ‘promote a norm that zero-day threats are OK in AI.’ Quite. It’s also interesting that it would probably only take ~$100,000 for a resourceful individual to re-create the full model quite quickly.

A few weeks ago, Deep Mind showed that their approach to beating human champions at GO can also beat the world’s best players at StarCraft, a game of IMperfect information which is much closer to real life human competitions than perfect information games like chess and GO. OpenAI has shown something similar with a similar game, DOTA.

*

Moore’s Law: what if a country spends 1-10% GDP pushing such curves?

The march of Moore’s Law is entangled in many predictions. It is true that in some ways Moore’s Law has flattened out recently…

… BUT specialised chips developed for machine learning and other adaptations have actually kept it going. This chart shows how it actually started long before Moore and has been remarkably steady for ~120 years (NVIDIA in the top right is specialised for deep learning)…

NB. This is a logarithmic scale so makes progress seem much less dramatic than the ~20 orders of magnitude it represents.

- Since Von Neumann and Turing led the development of the modern computer in the 1940s, the price of computation has got ~x10 cheaper every five years (so x100 per decade), so over ~75 years that’s a factor of about a thousand trillion (1015).

- The industry seems confident the graph above will continue roughly as it has for at least another decade, though not because of continued transistor doubling rates which has reached such a tiny nanometer scale that quantum effects will soon interfere with engineering. This means ~100-fold improvement before 2030 and combined with the ecosystem of entrepreneurs/VC/science investment etc this will bring many major disruptions even without significant progress with general intelligence.

- Dominant companies like Apple, Amazon, Google, Baidu, Alibaba etc (NB. no big EU players) have extremely strong incentives to keep this trend going given the impact of mobile computing / the cloud etc on their revenues.

- Computers will be ~10,000 times more powerful than today for the same price if this chart holds for another 20 years and ~1 million times more powerful for the same price than today if it holds for another 30 years. Today’s multi-billion dollar supercomputer performance would be available for ~$1,000, just as the supercomputer power of a few decades ago is now available in your smartphone.

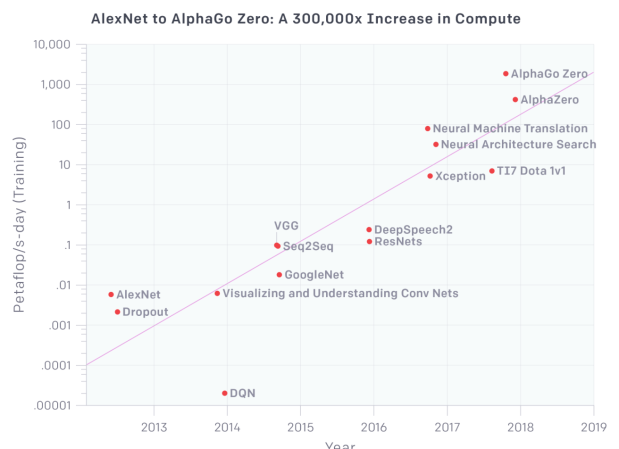

But there is another dimension to this trend. Look at this graph below. It shows the total amount of compute, in petaflop/s-days, that was used to train some selected AI projects using neural networks / deep learning.

‘Since 2012, the amount of compute used in the largest AI training runs has been increasing exponentially with a 3.5 month-doubling time (by comparison, Moore’s Law had an 18-month doubling period). Since 2012, this metric has grown by more than 300,000x (an 18-month doubling period would yield only a 12x increase)… The chart shows the total amount of compute, in petaflop/s-days, that was used to train selected results that are relatively well known, used a lot of compute for their time, and gave enough information to estimate the compute used. A petaflop/s-day (pfs-day) consists of performing 1015neural net operations per second for one day, or a total of about 1020operations. ‘ (Cf. OpenAI blog.)

The AlphaZero project in the top right is the recent Deep Mind project in which an AI system (a successor to the original AlphaGo that first beat human GO champions) zoomed by centuries of human knowledge on GO and chess in about one day of training.

Many dramatic breakthroughs in machine learning, particularly using neural networks (NNs), are open source. They are scaling up very fast. They will be networked together into ‘networks of networks’ and will become x10, x100, x1,000 more powerful. These NNs will keep demonstrating better than human performance in relatively narrowly defined tasks (like winning games) but these narrow definitions will widen unpredictably.

OpenAI’s blog showing the above graph concludes:

‘Overall, given the data above, the precedent for exponential trends in computing, work on ML specific hardware, and the economic incentives at play, we think it’d be a mistake to be confident this trend won’t continue in the short term. Past trends are not sufficient to predict how long the trend will continue into the future, or what will happen while it continues. But even the reasonable potential for rapid increases in capabilities means it is critical to start addressing both safety and malicious use of AI today. Foresight is essential to responsible policymaking and responsible technological development, and we must get out ahead of these trends rather than belatedly reacting to them.’ (Bold added)

This recent analysis of the extremely rapid growth of deep learning systems tries to estimate how long this rapid growth can continue and what interesting milestones may fall. It considers 1) the rate of growth of cost, 2) the cost of current experiments, and 3) the maximum amount that can be spent on an experiment in the future. Its rough answers are:

- ‘The cost of the largest experiments is increasing by an order of magnitude every 1.1 – 1.4 years.

- ‘The largest current experiment, AlphaGo Zero, probably cost about $10M.’

- On the basis of the Manhattan Project costing ~1% of GDP, that gives ~$200 billion for one AI experiment. Given the growth rate, we could expect a $200B experiment in 5-6 years.

- ‘There is a range of estimates for how many floating point operations per second are required to simulate a human brain for one second. Those collected by AI Impacts have a median of 1018 FLOPS (corresponding roughly to a whole-brain simulation using Hodgkin-Huxley neurons)’. [NB. many experts think 1018 is off by orders of magnitude and it could easily be x1,000 or more higher.]

- ‘So for the shortest estimates … we have already reached enough compute to pass the human-childhood milestone. For the median estimate, and the Hodgkin-Huxley estimates, we will have reached the milestone within 3.5 years.’

- We will not reach the bigger estimates (~1025FLOPS) within the 10 year window.

- ‘The AI-Compute trend is an extraordinarily fast trend that economic forces (absent large increases in GDP) cannot sustain beyond 3.5-10 more years. Yet the trend is also fast enough that if it is sustained for even a few years from now, it will sweep past some compute milestones that could plausibly correspond to the requirements for AGI, including the amount of compute required to simulate a human brain thinking for eighteen years, using Hodgkin Huxley neurons.’

I can’t comment on the technical aspects of this but one political/historical point. I think this analysis is wrong about the Manhattan Project (MP). His argument is the MP represents a reasonable upper-bound for what America might spend. But the MP was not constrained by money — it was mainly constrained by theoretical and engineering challenges, constraints of non-financial resources and so on. Having studied General Groves’ book (who ran the MP), he does not say money was a problem — in fact, one of the extraordinary aspects of the story is the extreme (to today’s eyes) measures he took to ensure money was not a problem. If more than 1% GDP had been needed, he’d have got it (until the intelligence came in from Europe that the Nazi programme was not threatening).

This is an important analogy. America and China are investing very heavily in AI but nobody knows — are there places at the edge of ‘breakthroughs with relatively narrow applications’ where suddenly you push ‘a bit’ and you get lollapalooza results with general intelligence? What if someone thinks — if I ‘only’ need to add some hardware and I can muster, say, 100 billion dollars to buy it, maybe I could take over the world? What if they’re right?

I think it is therefore more plausible to use the US defence budget at the height of the Cold War as a ‘reasonable estimate’ for what America might spend if they feel they are in an existential struggle. Washington knows that China is putting vast resources into AI research. If it starts taking over from Deep Mind and OpenAI as the place where the edge-of-the-art is discovered, then it WILL soon be seen as an existential struggle and there would rapidly be political pressures for a 1950s/1960s style ‘extreme’ response. So a reasonable upper bound might be at least 5-8 times bigger than 1% of GDP.

Further, unlike the nuclear race, an AGI race carries implications of not just ‘destroy global civilisation and most people’ but ‘potentially destroys ABSOLUTELY EVERYTHING not just on earth but, given time and the speed of light, everywhere’ — i.e potentially all molecules re-assembled in the pursuit of some malign energy-information optimisation process. Once people realise just how bad AGI could go if the alignment problem is not solved (see below), would it not be reasonable to assume that even more money than ~8% GDP will be found if/when this becomes a near-term fear of politicians?

Some in Silicon Valley who already have many billions at their disposal are already calculating numbers for these budgets. Surely people in Chinese intelligence are doodling the same as they listen to the week’s audio of Larry talking to Demis…?

*

General intelligence and safety

‘[R]ational systems exhibit universal drives towards self-protection, resource acquisition, replication and efficiency. Those drives will lead to anti-social and dangerous behaviour if not explicitly countered. The current computing infrastructure would be very vulnerable to unconstrained systems with these drives.’ Omohundro.

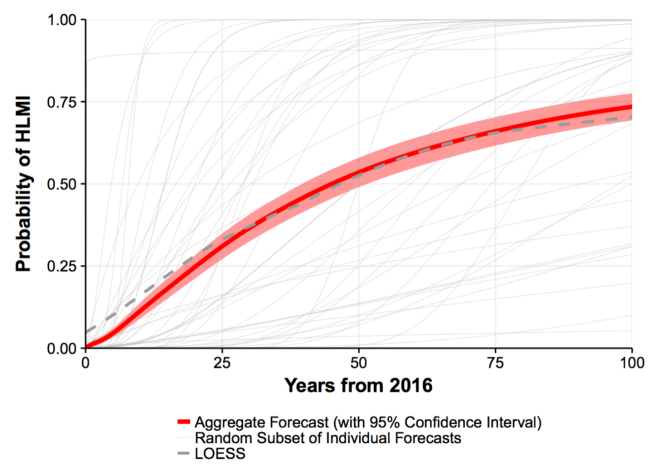

Shane Legg, co-founder and chief scientist of Deep Mind, said publicly a few years ago that there is a 50% probability that we will achieve human level AI by 2028, a 90% probability by 2050, and ‘I think human extinction will probably occur‘. Given Deep Mind’s progress since he said this it is surely unlikely he thinks the odds now are lower than 50% by 2028. Some at the leading edge of the field agree.

‘I think that within a few years we’ll be able to build an NN-based [neural network] AI (an NNAI) that incrementally learns to become at least as smart as a little animal, curiously and creatively learning to plan, reason and decompose a wide variety of problems into quickly solvable sub-problems. Once animal-level AI has been achieved, the move towards human-level AI may be small: it took billions of years to evolve smart animals, but only a few millions of years on top of that to evolve humans. Technological evolution is much faster than biological evolution, because dead ends are weeded out much more quickly. Once we have animal-level AI, a few years or decades later we may have human-level AI, with truly limitless applications. Every business will change and all of civilisation will change…

‘In 2050 there will be trillions of self-replicating robot factories on the asteroid belt. A few million years later, AI will colonise the galaxy. Humans are not going to play a big role there, but that’s ok. We should be proud of being part of a grand process that transcends humankind.’ Schmidhuber, one of the pioneers of ML, 2016.