Britain could contribute huge value to the world by leveraging existing assets, including scientific talent and how the NHS is structured, to push the frontiers of a rapidly evolving scientific field — genomic prediction — that is revolutionising healthcare in ways that give Britain some natural advantages over Europe and America. We should plan for free universal ‘SNP’ genetic sequencing as part of a shift to genuinely preventive medicine — a shift that will lessen suffering, save money, help British advanced technology companies in genomics and data science/AI, make Britain more attractive for scientists and global investment, and extend human knowledge in a crucial field to the benefit of the whole world.

‘SNP’ sequencing means, crudely, looking at the million or so most informative markers or genetic variants without sequencing every base pair in the genome. SNP sequencing costs ~$50 per person (less at scale), whole genome sequencing costs ~$1,000 per person (less at scale). The former captures most of the predictive power now possible at 1/20th of the cost of the latter.

*

Background: what seemed ‘sci fi’ ~2010-13 is now reality

In my 2013 essay on education and politics, I summarised the view of expert scientists on genetics (HERE between pages 49-51, 72-74, 194-203). Although this was only a small part of the essay most of the media coverage focused on this, particularly controversies about IQ.

Regardless of political affiliation most of the policy/media world, as a subset of ‘the educated classes’ in general, tended to hold a broadly ‘blank slate’ view of the world mostly uninformed by decades of scientific progress. Technical terms like ‘heritability’, which refers to the variance in populations, caused a lot of confusion.

When my essay hit the media, fortunately for me the world’s leading expert, Robert Plomin, told hacks that I had summarised the state of the science accurately. (I never tried to ‘give my views on the science’ as I don’t have ‘views’ — all people like me can try to do with science is summarise the state of knowledge in good faith.) Quite a lot of hacks then spent some time talking to Plomin and some even wrote about how they came to realise that their assumptions about the science had been wrong (e.g Gaby Hinsliff).

Many findings are counterintuitive to say the least. Almost everybody naturally thinks that ‘the shared environment’ in the form of parental influence ‘obviously’ has a big impact on things like cognitive development. The science says this intuition is false. The shared environment is much less important than we assume and has very little measurable effect on cognitive development: e.g an adopted child who does an IQ test in middle age will show on average almost no correlation with the parents who brought them up (genes become more influential as you age). People in the political world assumed a story of causation in which, crudely, wealthy people buy better education and this translates into better exam and IQ scores. The science says this story is false. Environmental effects on things like cognitive ability and education achievement are almost all from what is known as the ‘non-shared environment’ which has proved very hard to pin down (environmental effects that differ for children, like random exposure to chemicals in utero). Further, ‘The case for substantial genetic influence on g [g = general intelligence ≈ IQ] is stronger than for any other human characteristic’ (Plomin) and g/IQ has far more predictive power for future education than class does. All this has been known for years, sometimes decades, by expert scientists but is so contrary to what well-educated people want to believe that it was hardly known at all in ‘educated’ circles that make and report on policy.

Another big problem is that widespread ignorance about genetics extends to social scientists/economists, who are much more influential in politics/government than physical scientists. A useful heuristic is to throw ~100% of what you read from social scientists about ‘social mobility’ in the bin. Report after report repeats the same clichés, repeats factual errors about genetics, and is turned into talking points for MPs as justification for pet projects. ‘Kids who can read well come from homes with lots of books so let’s give families with kids struggling to read more books’ is the sort of argument you read in such reports without any mention of the truth: children and parents share genes that make them good at and enjoy reading, so causation is operating completely differently to the assumptions. It is hard to overstate the extent of this problem. (There are things we can do about ‘social mobility’, my point is Insider debate is awful.)

A related issue is that really understanding the science requires serious understanding of statistics and, now, AI/machine learning (ML). Many social scientists do not have this training. This problem will get worse as data science/AI invades the field.

A good example is ‘early years’ and James Heckman. The political world is obsessed with ‘early years’ such as Sure Start (UK) and Head Start (US). Politicians latch onto any ‘studies’ that seem to justify it and few have any idea about the shocking state of the studies usually quoted to justify spending decisions. Heckman has published many papers on early years and they are understandably widely quoted by politicians and the media. Heckman is a ‘Nobel Prize’ winner in economics. One of the world’s leading applied mathematicians, Professor Andrew Gelman, has explained how Heckman has repeatedly made statistical errors in his papers but does not correct them: cf. How does a Nobel-prize-winning economist become a victim of bog-standard selection bias? This really shows the scale of the problem: if a Nobel-winning economist makes ‘bog standard’ statistical errors that confuse him about studies on pre-school, what chance do the rest of us in the political/media world have?

Consider further that genomics now sometimes applies very advanced mathematical ideas such as ‘compressed sensing’. Inevitably few social scientists can judge such papers but they are overwhelmingly responsible for interpreting such things for ministers and senior officials. This is compounded by the dominance of social scientists in Whitehall units responsible for data and evidence. Many of these units are unable to provide proper scientific advice to ministers (I have had personal experience of this in the Department for Education). Two excellent articles by Duncan Watts recently explained fundamental problems with social science and what could be done (e.g a much greater focus on successful prediction) but as far as I can tell they have had no impact on economists and sociologists who do not want to face their lack of credibility and whose incentives in many ways push them towards continued failure (Nature paper HERE, Science paper HERE — NB. the Department for Education did not even subscribe to the world’s leading science journals until I insisted in 2011).

1) The problem that the evidence for early years is not what ministers and officials think it is is not a reason to stop funding but I won’t go into this now. 2) This problem is incontrovertible evidence, I think, of the value of an alpha data science unit in Downing Street, able to plug into the best researchers around the world, and ensure that policy decisions are taken on the basis of rational thinking and good science or, just as important, everybody is aware that they have to make decisions in the absence of this. This unit would pay for itself in weeks by identifying flawed reasoning and stopping bad projects, gimmicks etc. Of course, this idea has no chance with those now at the top of Government and the Cabinet Office would crush such a unit as it would threaten the traditional hierarchy. One of the arguments I made in my essay was that we should try to discover useful and reliable benchmarks for what children of different abilities are really capable of learning and build on things like the landmark Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth. This obvious idea is anathema to the education policy world where there is almost no interest in things like SMPY and almost everybody supports the terrible idea that ‘all children must do the same exams’ (guaranteeing misery for some and boredom/time wasting for others). NB. Most rigorous large-scale educational RCTs are uninformative. Education research, like psychology, produces a lot of what Feynman called ‘cargo cult science’.

Since 2013, genomics has moved fast and understanding in the UK media has changed probably faster in five years than over the previous 35 years. As with the complexities of Brexit, journalists have caught up with reality much better than MPs. It’s still true that almost everything written by MPs about ‘social mobility’ is junk but you could see from the reviews of Plomin’s recent book, Blueprint, that many journalists have a much better sense of the science than they did in 2013. Rare good news, though much more progress is needed…

*

What’s happening now?

In 2013 it was already the case that the numbers on heritability derived from twin and adoption studies were being confirmed by direct inspection of DNA — therefore many of the arguments about twin/adoption studies were redundant — but this fact was hardly known.

I pointed out that the field would change fast. Both Plomin and another expert, Steve Hsu, made many predictions around 2010-13 some of which I referred to in my 2013 essay. Hsu is a physics professor who is also one of the world’s leading researchers on genomics.

Hsu predicted that very large samples of DNA would allow scientists over the next few years to start identifying the actual genes responsible for complex traits, such as diseases and intelligence, and make meaningful predictions about the fate of individuals. Hsu gave estimates of the sample sizes that would be needed. His 2011 talk contains some of these predictions and also provides a physicist’s explanation of ‘what is IQ measuring’. As he said at Google in 2011, the technology is ‘right on the cusp of being able to answer fundamental questions’ and ‘if in ten years we all meet again in this room there’s a very good chance that some of the key questions we’ll know the answers to’. His 2014 paper explains the science in detail. If you spend a little time looking at this, you will know more than 99% of high status economists gabbling on TV about ‘social mobility’ saying things like ‘doing well on IQ tests just proves you can do IQ tests’.

In 2013, the world of Westminster thought this all sounded like science fiction and many MP said I sounded like ‘a mad scientist’. Hsu’s predictions have come true and just five years later this is no longer ‘science fiction’. (Also NB. Hsu’s blog was one of the very few places where you would have seen discussion of CDOs and the 2008 financial crash long BEFORE it happened. I have followed his blog since ~2004 and this from 2005, two years before the crash started, was the first time I read about things like ‘synthetic CDOs’: ‘we have yet another ill-understood casino running, with trillions of dollars in play’. The quant-physics network had much better insight into the dynamics behind the 2008 Crash than high status mainstream economists like Larry Summers responsible for regulation.)

His group and others have applied machine learning to very large genetic samples and built predictors of complex traits. Complex traits like general intelligence and most diseases are ‘polygenic’ — they depend on many genes each of which contributes a little (unlike diseases caused by a single gene).

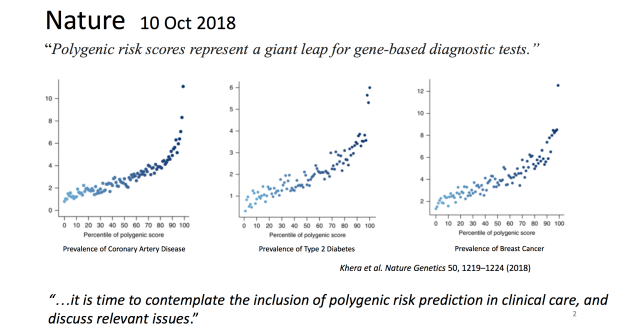

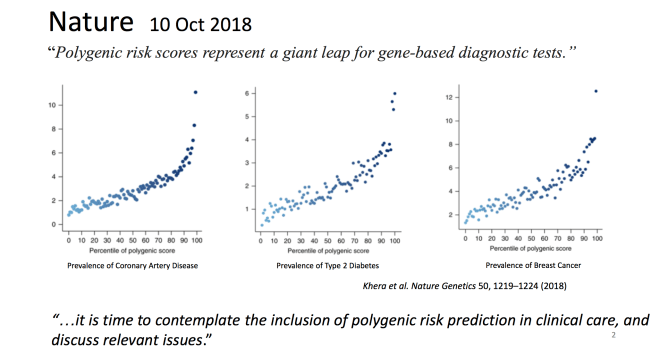

‘There are now ~20 disease conditions for which we can identify, e.g, the top 1% outliers with 5-10x normal risk for the disease. The papers reporting these results have almost all appeared within the last year or so.’

For example, the height predictor ‘captures nearly all of the predicted SNP heritability for this trait — actual heights of most individuals in validation tests are within a few cm of predicted heights.’ Height is similar to IQ — polygenic and similar heritability estimates.

These predictors have been validated with out-of-sample tests. They will get better and better as more and more data is gathered about more and more traits.

This enables us to take DNA from unborn embryos, do SNP genetic sequencing costing ~$50, and make useful predictions about the odds of the embryo being an outlier for diseases like atrial fibrillation, diabetes, breast cancer, or prostate cancer. NB. It is important that we do not need to sequence the whole genome to do this (see below). We will also be able to make predictions about outliers in cognitive abilities (the high and low ends). (My impression is that predicting Alzheimers is still hampered by a lack of data but this will improve as the data improves.)

There are many big implications. This will obviously revolutionise IVF. ~1 million IVF embryos per year are screened worldwide using less sophisticated tests. Instead of picking embryos at random, parents will start avoiding outliers for disease risks and cognitive problems. Rich people will fly to jurisdictions offering the best services.

Forensics is being revolutionised. First, DNA samples can be used to give useful physical descriptions of suspects because you can identify ethnic group, height, hair colour etc. Second, ‘cold cases’ are now routinely being solved because if a DNA sample exists, then the police can search for cousins of the perpetrator from public DNA databases, then use the cousins to identify suspects. Every month or so now in America a cold case murder is solved and many serial killers are being found using this approach — just this morning I saw what looks to be another example just announced, a murder of an 11 year-old in 1973. (Some companies are resisting this development but they will, I am very confident, be smashed in court and have their reputations trashed unless they change policy fast. The public will have no sympathy for those who stand in the way.)

Hsu recently attended a conference in the UK where he presented some of these ideas to UK policy makers. He wrote this blog about the great advantages the NHS has in developing this science.

‘The UK could become the world leader in genomic research by combining population-level genotyping with NHS health records… The US private health insurance system produces the wrong incentives for this kind of innovation: payers are reluctant to fund prevention or early treatment because it is unclear who will capture the ROI [return on investment]… The NHS has the right incentives, the necessary scale, and access to a deep pool of scientific talent. The UK can lead the world into a new era of precision genomic medicine.

‘NHS has already announced an out-of-pocket genotyping service which allows individuals to pay for their own genotyping and to contribute their health + DNA data to scientific research. In recent years NHS has built an impressive infrastructure for whole genome sequencing (cost ~$1k per individual) that is used to treat cancer and diagnose rare genetic diseases. The NHS subsidiary Genomics England recently announced they had reached the milestone of 100k whole genomes…

‘At the meeting, I emphasized the following:

1. NHS should offer both inexpensive (~$50) genotyping (sufficient for risk prediction of common diseases) along with the more expensive $1k whole genome sequencing. This will alleviate some of the negative reaction concerning a “two-tier” NHS, as many more people can afford the former.

2. An in-depth analysis of cost-benefit for population wide inexpensive genotyping would likely show a large net cost savings: the risk predictors are good enough already to guide early interventions that save lives and money. Recognition of this net benefit would allow NHS to replace the $50 out-of-pocket cost with free standard of care.’ (Emphasis added)

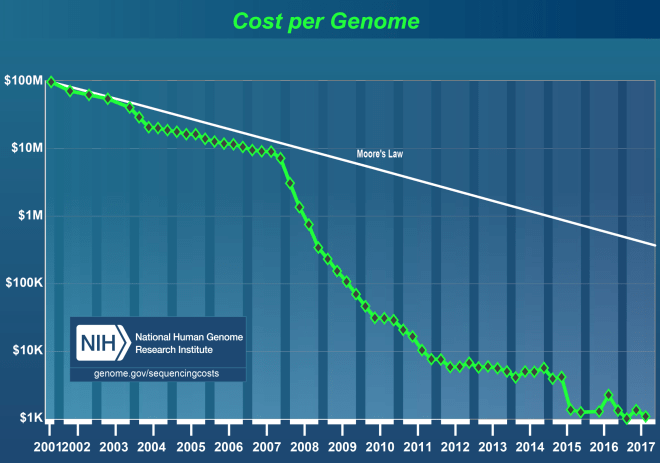

NB. In terms of the short-term practicalities it is important that whole genome sequencing costs ~$1,000 (and falling) but is not necessary: a version 1/20th of the cost, looking just at the most informative genetic variants, captures most of the predictive benefits. Some have incentives to distort this, such as companies like Illumina trying to sell expensive machines for whole genome sequencing, which can distort policy — let’s hope officials are watching carefully. These costs will, obviously, keep falling.

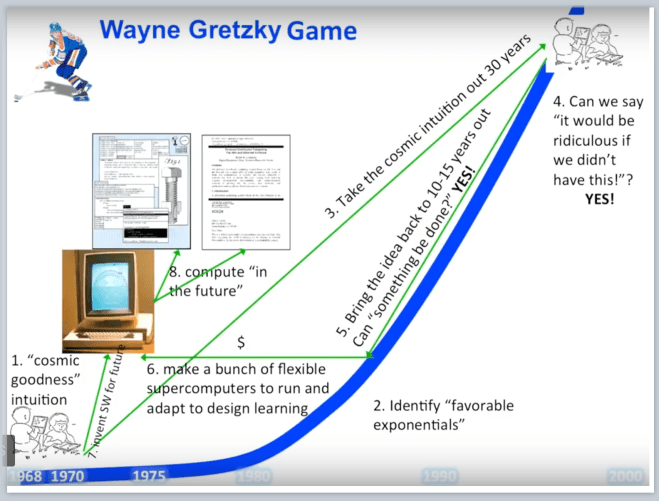

This connects to an interesting question… Why was the likely trend in genomics clear ~2010 to Plomin, Hsu and others but invisible to most? Obviously this involves lots of elements of expertise and feel for the field but also they identified FAVOURABLE EXPONENTIALS. Here is the fall in the cost of sequencing a genome compared to Moore’s Law, another famous exponential. The drop over ~18 years has been a factor of ~100,000. Hsu and Plomin could extrapolate that over a decade and figure out what would be possible when combined with other trends they could see. Researchers are already exploring what will be possible as this trend continues.

Identifying favourable exponentials is extremely powerful. Back in the early 1970s, the greatest team of computer science researchers ever assembled (PARC) looked out into the future and tried to imagine what could be possible if they brought that future back to the present and built it. They were trying to ‘compute in the future’. They created personal computing. (Chart by Alan Kay, one of the key researchers — he called it ‘the Gretzky game’ because of Gretzky’s famous line ‘I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.’ The computer is the Alto, the first personal computer that stunned Steve Jobs when he saw a demo. The sketch on the right is of children using a tablet device that Kay drew decades before the iPad was launched.)

Hopefully the NHS and Department for Health will play ‘the Gretzky game’, take expert advice from the likes of Plomin and Hsu and take this opportunity to make the UK a world leader in one of the most important frontiers in science.

- We can imagine everybody in the UK being given valuable information about their health for free, truly preventive medicine where we target resources at those most at risk, and early (even in utero) identification of risks.

- This would help bootstrap British science into a stronger position with greater resources to study things like CRISPR and the next phase of this revolution — editing genes to fix problems, where clinical trials are already showing success.

- It would also give a boost to British AI/data science companies — the laws, rules on data etc should be carefully shaped to ensure that British companies (not Silicon Valley or China) capture most of the financial value (though everybody will gain from the basic science).

- These gains would have positive feedback effects on each other, just as investment in basic AI/ML research will have positive feedback effects in many industries.

- I have argued many times for the creation of a civilian UK ‘ARPA’ — a centre for high-risk-high-payoff research that has been consistently blocked in Whitehall (see HERE for an account of how ARPA-PARC created the internet and personal computing). This fits naturally with Britain seeking to lead in genomics/AI. Thinking about this is part of a desperately needed overall investigation into the productivity of the British economy and the ecosystem of universities, basic science, venture capital, startups, regulation (data, intellectual property etc) and so on.

There will also be many controversies and problems. The ability to edit genomes — and even edit the germline with ‘gene drives’ so all descendants have the same copy of the gene — is a Promethean power implying extreme responsibilities. On a mundane level, embracing new technology is clearly hard for the NHS with its data infrastructure. Almost everyone I speak to using the NHS has had similar problems that I have had — nightmares with GPs, hospitals, consultants et al being able to share data and records, things going missing, etc. The NHS will be crippled if it can’t fix this, but this is another reason to integrate data science as a core ‘utility’ for the NHS.

On a political note…

Few scientists and even fewer in the tech world are aware of the EU’s legal framework for regulating technology and the implications of the recent Charter of Fundamental Rights (the EU’s Charter, NOT the ECHR) which gives the Commission/ECJ the power to regulate any advanced technology, accelerate the EU’s irrelevance, and incentivise investors to invest outside the EU. In many areas, the EU regulates to help the worst sort of giant corporate looters defending their position against entrepreneurs. Post-Brexit Britain will be outside this jurisdiction and able to make faster and better decisions about regulating technology like genomics, AI and robotics. Prediction: just as Insiders now talk of how we ‘dodged a bullet’ in staying out of the euro, within ~10 years Insiders will talk about being outside the Charter/ECJ and the EU’s regulation of data/AI in similar terms (assuming Brexit happens and UK politicians even try to do something other than copy the EU’s rules).

China is pushing very hard on genomics/AI and regards such fields as crucial strategic ground for its struggle for supremacy with America. America has political and regulatory barriers holding it back on genomics that are much weaker here. Britain cannot stop the development of such science. Britain can choose to be a backwater, to ignore such things and listen to MPs telling fairy stories while the Chinese plough ahead, or it can try to lead. But there is no hiding from the truth and ‘for progress there is no cure’ (von Neumann). We will never be the most important manufacturing nation again but we could lead in crucial sub-fields of advanced technology. As ARPA-PARC showed, tiny investments can create entire new industries and trillions of dollars of value.

Sadly most politicians of Left and Right have little interest in science funding with tremendous implications for future growth, or the broader question of productivity and the ecosystem of science, entrepreneurs, universities, funding, regulation etc, and we desperately need institutions that incentivise politicians and senior officials to ‘play the Gretzky game’. The next few months will be dominated by Brexit and, hopefully, the replacement of the May/Hammond government. Those thinking about the post-May landscape and trying to figure out how to navigate in uncharted and turbulent waters should focus on one of the great lessons of politics that is weirdly hard for many MPs to internalise: the public rewards sustained focus on their priorities!

One of the lessons of the 2016 referendum (that many Conservative MPs remain desperate not to face) is the political significance of the NHS. The concept described above is one of those concepts in politics that maximises positive futures for the force that adopts it because it draws on multiple sources of strength. It combines, inter alia, all the political benefits of focus on the NHS, helping domestic technology companies, incentivising global investment, doing something that shows the world that Britain is (contra the May/Hammond outlook) open to science and high skilled immigrants, it is based on intrinsic advantages that Europe and America will find hard to overcome over a decade, it supplies (NB. MPs/spads) a never-ending string of heart-wrenching good news stories, and, very rarely in SW1, those pushing it would be seen as leading something of global importance. It will, therefore, obviously be rejected by a section of Conservative MPs who much prefer to live in a parallel world, who hate anything to do with science and who are ignorant about how new industries and wealth are really created. But for anybody trying to orient themselves to reality, connect themselves to sources of power, and thinking ‘how on earth could we clamber out of this horror show’, it is an obvious home run…

NB. It ought to go without saying that turning this idea into a political/government success requires focus on A) the NHS, health, science, NOT getting sidetracked into B) arguments about things like IQ and social mobility. Over time, the educated classes will continue to be dragged to more realistic views on (B) but this will be a complex process entangled with many hysterical episodes. (A) requires ruthless focus…

Please leave comments, fix errors below. I have not shown this blog in draft to Plomin or Hsu who obviously are not responsible for my errors.

Further reading

Plomin’s excellent new book, Blueprint. I would encourage journalists who want to understand this subject to speak to Plomin who works in London and is able to explain complex technical subjects to very confused arts graduates like me.

On the genetic architecture of intelligence and other quantitative traits, Hsu 2014.

Cf. this thread by researcher Paul Pharaoh on breast cancer.