‘The combination of physics and politics could render the surface of the earth uninhabitable… [Technological progress] gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we have known them, cannot continue.’ John von Neumann, one of the 20th Century’s most important mathematicians, one of the two most responsible for developing digital computers, central to Manhattan Project etc.

‘Politics is always like visiting a country one does not know with people whom one does not know and whose reactions one cannot predict. When one person puts a hand in his pocket, the other person is already drawing his gun, and when he pulls the trigger the first one fires and it is too late then to ask whether the requirements of common law with regard to self-defence apply, and since common law is not effective in politics people are very, very quick to adopt an aggressive defence.’ Bismarck, 1879.

*

Below is a review of Graham Allison’s book, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. Allison’s book is particularly interesting given what is happening with North Korea and Trump. It is partly about the most urgent question: whether and how humanity can survive the collision between science and politics.

Beneath the review are a few other thoughts on the book and its themes. I will also post some notes on stuff connecting ideas about advanced technology and strategy (conventional and nuclear) including notes from the single best book on nuclear strategy, Payne’s The Great American Gamble: deterrence theory and practice from the Cold War to the twenty-first century. If you want to devote your life to a cause with maximum impact, then studying this book is a good start and it also connects to debates on other potential existential threats such as biological engineering and AI.

Payne’s book connects directly to Allison’s. Allison focuses a lot on the circumstances in which crises could spin out of control and end in US-China war. Payne’s book is the definitive account of nuclear strategy and its intellectual and practical problems. Payne’s book in a nutshell: 1) politicians and most senior officials operate with the belief that there is a dependable ‘rational’ basis for successful deterrence in which ‘rational’ US opponents will respond prudently and cautiously to US nuclear deterrence threats; 2) the re-evaluation of nuclear strategy in expert circles since the Cold War exposes the deep flaws of Cold War thinking in general and the concept of ‘rational’ deterrence in particular (partly because strategy was dangerously influenced by ideas about rationality from economics). Expert debate has not permeated to most of those responsible or the media. Trump’s language over North Korea and the media debate about it are stuck in the language of Cold War deterrence.

I would bet that no UK Defence Secretary has read Payne’s book. (Have the MoD PermSecs? The era of Michael Quinlan has long gone as the Iraq inquiries revealed.) What emerges from UK Ministers suggests they are operating with Cold War illusions. If you think I’m probably too pessimistic, then ponder this comment by Professor Allison who has spent half a century in these circles: ‘Over the past decade, I have yet to meet a senior member of the US national security team who had so much as read the official national security strategies’ (emphasis added). NB. he is referring to reading the official strategies, not the explanations of why they are partly flawed!

This of course relates to the theme of much I have written: the dangers created by the collision of science and markets with dysfunctional individuals and political institutions, and the way the political-media system actively suppresses thinking about, and focus on, what’s important.

Priorities are fundamental to politics because of inevitable information bottlenecks: these bottlenecks can be transformed by rare good organisation but they cannot be eradicated. People are always asking ‘how could the politicians let X happen with Y?’ where Y is something important. People find it hard to believe that Y is not the focus of serious attention and therefore things like X are bound to happen all the time. People like Osborne and Clegg are focused on some magazine profile, not Y. The subject of nuclear command and control ought to make people realise that their mental models for politics are deeply wrong. It is beyond doubt that politicians do not even take the question of accidental nuclear war seriously, so a fortiori there is no reason to have confidence in their general approach to priorities.

If you think of politics as ‘serious people focusing seriously on the most important questions’, which is the default mode of most educated people and the media (but not the less-educated public which has better instincts), then your model of reality is badly wrong. A more accurate model is: politics is a system that 1) selects against skills needed for rigorous thinking and for qualities such as groupthink and confirmation bias, 2) incentivises a badly selected set of people to consider their career not the public interest, 3) drops them into dysfunctional institutions with no relevant training and poor tools, 4) centralises vast amounts of power in the hands of these people and institutions in ways we know are bound to cause huge errors, and 5) provides very weak (and often damaging) feedback so facing reality is rare, learning is practically impossible, and system reform is seen as a hostile act by political parties and civil services worldwide.

I meant to publish this a few days ago on ‘Petrov day’, the anniversary of 26 September 1983 when Petrov saw US nuclear missiles heading for Russia on his screen but in a snap decision without consultation he decided not to inform his superiors, guessing it was some sort of technical error and not wanting to risk catastrophic escalation. (Petrov died a few weeks ago.) I forgot to post but my point is: we will not keep getting lucky like that, and our odds worsen with every week that the political system works as it does. The cumulative probability of disaster grows alarmingly even if you assume a small chance of disaster. For example, a 1% chance of wipeout per year means the probability of wipeout is about 20% within 20 years, about 50% within 70 years, and about two-thirds within a century. Given what we now know it’s reasonable to plan on the basis that the chance of a nuclear accident of some sort leading to mass destruction is at least 1% per year. A 1:30 chance per year means a ~97% chance of wipeout in a century…

*

Review of Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, by Graham Allison

Every day on his way to work at Harvard, Professor Allison wondered how the reconstruction of the bridge over Boston’s Charles River could take years while in China bigger bridges are replaced in days. His book tells the extraordinary story of China’s transformation since Deng abandoned Mao’s catastrophic Stalinism, and considers whether the story will end in war between China and America.

China erects skyscrapers in weeks while Parliament delays Heathrow expansion for over a decade. The EU discusses dumb rules made 60 years ago while China produces a Greece-sized economy every 16 weeks. China’s economy doubles roughly every seven years; it is already the size of America’s and will likely dwarf it in 20 years. More serious than Europe, it invests this growth in education and technology from genetic engineering to artificial intelligence.

Allison analyses the formidable President Xi, who has known real suffering and is very different to western leaders obsessed with the frivolous spin cycles of domestic politics. Xi’s goal is to ensure that China’s renaissance returns it to its position as the richest, strongest and most advanced culture on earth. Allison asks: will the US-China relationship repeat the dynamics between Athens and Sparta that led to war in 431 bc or might it resemble the story of the British-American alliance in the 20th century?

In Thucydides’ history the dynamic growth of Athens caused such fear that, amid confusing signals in an escalating crisis, Sparta gambled on preventive war. Similarly, after Bismarck unified Germany in 1870-71, Europe’s balance of power was upended. In summer 1914, the leaderships of all Great Powers were overwhelmed by confusing signals amid a rapidly escalating crisis. The prime minister doodled love letters to his girlfriend as the cabinet discussed Ireland, and European civilisation tottered over the brink.

Allison discusses how America, China and Taiwan [or Korea] might play the roles of Britain, Germany and Belgium. China has invested in weapons with powerful asymmetric advantages: cheap missiles can sink an aircraft carrier costing billions, and cyber weapons could negate America’s powerful space and communication infrastructure. American war-games often involve bombing Chinese coastal installations. How far might it escalate?

Nuclear weapons increase destructive power a million-fold and give a leader just minutes to decide whether a (possibly false) warning justifies firing weapons that would destroy civilisation, while relying on the same sort of hierarchical decision-making processes that failed in the much slower 1914 crisis.

Terrifying near misses have already happened, and we have been saved by individuals’ snap judgments. They have occurred, luckily, during episodes of relative calm. Similar incidents during an intense crisis could spark catastrophe. The Pentagon hoped that technology would bring ‘information dominance’: instead, technology accelerates crises and overwhelms decisions. Real and virtual robots will fight battles and influence minds faster than traditional institutions can follow.

Allison hopes Washington will rediscover its 1940s seriousness, when it built a strategy and institutions to contain Stalin. He suggests abandoning ‘containment’, which is unlikely to work in the same way against capitalist China as it did against Soviet Russia. It could drop security guarantees to Taiwan to lower escalation risks. It could promote new institutions to tackle destructive technology and terrorism. Since China will upend post-1945 institutions anyway, why not try to shape what comes next together? Perhaps, channelling Sun Tzu, the West could avoid defeat by not trying to ‘win’.

It is hard to see how the necessary leadership might emerge.

We need government teams capable of the rare high performance we see in George Mueller’s Nasa, which put man on the moon; or in Silicon Valley, entrepreneurs such as Sam Altman and Patrick Collison. This means senior politicians and officials of singular ability and with different education, training and experience. It means extremely adaptive institutions and state-of-the-art tools, not the cabinet processes that failed in 1914. It means breaking the power of self-absorbed parties and bureaucracies that evolved before nuclear physics and the internet.

New leaders must build institutions for global cooperation that can transcend Thucydides’ dynamics. For example, the plan of Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s CEO, to build a permanent moon base in which countries work together to harness the resources of the solar system is the sort of project that could create an alternative focus to nationalist antagonism.

The scale of change seems impossible, yet technology gives us no choice — we must try to escape our evolutionary origins, since we cannot survive repeated roulette with advanced technology. Churchill wrote how in 1914 governments drifted into ‘fathomless catastrophe’ in ‘a kind of dull cataleptic trance’. Western leaders are in another such trance. Unless new forces evolve outside closed political systems and force change we will suffer greater catastrophe; it’s just a matter of when.

I hope people like Jeff Bezos read this timely book and resolve to build the political forces we need.

(Originally appeared in The Spectator.)

*

A few other thoughts

I’ve got some quibbles, such as interpretations of Thucydides, but I won’t go into those.

There are many issues in it I did not have time to mention in a short review…

1. Nuclear crises / accidents

In the context of US-China crises, it is very instructive to consider some of the most dangerous episodes of the Cold War that remained secret at the time.

Here are some of the near misses that have been declassified (see this timeline from Future of Life Institute).

- 24 January 1961. A US bomber broke up and dropped two hydrogen bombs on North Carolina. Five of six safety devices failed. ‘By the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted’ (Defence Secretary Robert McNamara).

- 25 October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. A sabotage alarm was triggered at a US base. Faulty wiring meant that the alarm triggered the take-off of nuclear armed US planes. Fortunately they made contact with the ground and were stood down. The alarm had been triggered by a bear — yes, a bear, like in a Simpsons episode — pottering around outside the base. This was one of many incidents during this crisis, including one base where missiles and codes were mishandled such that a single person could have launched.

- 27 October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. A Soviet submarine was armed with nuclear weapons. It was cornered by US ships which dropped depth charges. It had no contact with Moscow for days and had no idea if war had already broken out. Malfunctioning systems meant carbon dioxide poisoning and crew were fainting. In panic the captain ordered a nuclear missile fired. Orders said that three officers had to agree. Only two did. Vasili Arkhipov said No. It was not known until after the collapse of the Soviet Union that there were also tactical nuclear missiles deployed to Cuba and, for the only time, under direct authority of field commanders who could fire without further authority from Moscow, so if the US had decided to attack Cuba, as many urged JFK to do, there is a reasonable chance that local commanders would have begun a nuclear exchange. Castro wanted these missiles, unknown to America, transferred to Cuban control. Fortunately, Mikoyan, the Soviet in charge on the ground, witnessed Castro’s unstable character and decided not to transfer these missiles to his control. The missiles were secretly returned to Russia shortly after.

- 1 August 1974. A warning of the danger of allowing one person to give a catastrophic order: Nixon was depressed, drinking heavily, and unstable so Defense Secretary Schlesinger told the Joint Chiefs to come to him in the event of any order to fire nuclear weapons.

- 9 November 1979. NORAD thought there was a large-scale Soviet nuclear attack. Planes were scrambled and ICBM crews put on highest alert. The National Security Adviser was called at home. He looked at his wife asleep and decided not to wake her as they would shortly both be dead and he turned his mind to calling President Carter about plans for massive retaliation before he died. After 6 minutes no satellite data confirmed launches. Decisions were delayed. It turned out that a technician had accidentally input a training program which played through the computer system as if it were a real attack. (There were other similar incidents.)

- 26 September 1983. A month after the Soviet Union shot down a Korean passenger jet and at a time of international tension, a Soviet satellite showed America had launched five nuclear missiles. The data suggested the satellite was working properly but the officer on duty, Stanilov Petrov, decided to report it to his superiors as a false alarm without knowing if it was true. It turned out to be an odd effect of sun glinting off clouds that fooled the system.

- 2-11 November 1983. NATO ran a large wargame with a simulation of DEFCON 1 and coordinated attack on the Soviet Union. The war-game was so realistic that Soviet intelligence thought it was a cover for a real attack and Soviet missiles were placed on high alert. On 11 November the Soviets intercepted a message saying US missiles had launched. Fortunately, incidents such as 26 September 1983 did not randomly occur during this 10 days.

- 25 January 1995. The Russian system detected the launch of a missile off the coast of Norway that was thought to be a US submarine launch. The warning went to Yeltsin who activated his ‘nuclear football’ and retrieved launch codes. There was no corroboration from satellites. Norway had actually reached a scientific rocket and somehow this was not notified properly in Russia.

- 29-30 August 2007. Six US nuclear weapons were accidentally loaded into a B52 which was left unguarded overnight, flown to another base where it was left unguarded for another nine hours before ground crew realised what they were looking at. For 36 hours nobody realised the missiles were missing.

- 23 October 2010. The US command and control system responsible for detecting and stopping unauthorised launches lost all control of 50 ICBMs for an hour because of communication failure caused by a dodgy component.

- A 2013 monitoring exercise found the US nuclear command and control system generally shambolic. Staff were found to be on drugs and otherwise unsuitable, the system was deemed unfit to cope with a major hack, and the commander of the ICBM force was compromised by a classic KGB ‘honey trap’ (when I lived in Moscow I met some of the women who worked on such operations and I’d bet >90% of male UK Ministers/PermSecs would throw themselves at them faster than you can say ‘honey trap’).

This is just a sample. The full list still understates the scale of luck we have had in at least two ways. First, the data is mostly from America because America is a more open society. The most sensible assumption is that there have been more incidents in Russia than we know about. Second, there is a selection bias towards older incidents that have been declassified.

Right now there are hundreds of missiles on ‘hair-trigger’ alert for launch within minutes. Decisions about how reliable a warning is and whether to fire must all be taken within minutes. This makes the whole world vulnerable to accidents, unauthorised use, unhinged leaders, and false alarms. This situation could get worse. China’s missiles are not on hair-trigger alert but the Chinese military is pushing to change this. Adding a third country operating like this would make the system even more unstable. It also seems very likely that proliferation will continue to spread. The West preaches non-proliferation at non-nuclear countries but this unsurprisingly is not persuasive.

2. China’s weaknesses, including the tension between informational openness needed for growth and its political dangers

During the Cold War, many people from different political perspectives were agreed on one thing: that the Soviet Union was much stronger than it later turned out to have been. This view was so powerful that people like Andy Marshall, the founder and multi-decade head of the Office of Net Assessment, struggled to find support for his argument that the CIA and Pentagon were systematically overstating the strength of the Soviet economy and understating the burden of defence spending. They had, of course, strong bureaucratic reasons to do so: a more dangerous enemy was the best argument for more funding. It is important to keep in mind this potential error viz China.

1929 and 2008 each had profound effects on US politics. China, interestingly, was not as badly hit by 2008 as the West. What is the probability that it will continue to avoid an economic crisis somewhere between a serious recession and a 1929/2008-style event over the next say 20 years? If it does experience such a shock, how effective will its political institutions be in coping relative to those of America’s and Britain’s over the long-term? Might debt and bad financial institutions create a political crisis serious enough to threaten the legitimacy of the regime? Might other problems such as secession movements (perhaps combined with terrorism) cause an equivalently serious political crisis? After all, historically the country has fallen apart repeatedly and this is the great fear of its leaders.

China also has serious resource vulnerabilities. It has to import most of its energy. It has serious water shortages. It has serious ecological crises. It has serious corruption problems. It has a rapidly ageing population. Although it, unlike the EU, has built brilliant private companies to rival Google et al, its state-owned enterprises (with special phones on CEO desks for Communist Party instructions) control gigantic resources and are not run as well as Google or Alibaba. There has been significant emigration of educated Chinese particularly to America where they buy houses and educate their children (Xi himself quietly sent a daughter to Harvard). Many of these tensions result in occasional public outcries that the regime carefully appeases. These problems are not trivial to solve even for very competent people who don’t have to worry about elections.

In terms of the risks of war and escalation over flashpoints like Korea or Taiwan, major internal crises like a financial crash might easily make it more likely that an external crisis escalates out of control. When regimes face crises of legitimacy they often, for obvious evolutionary reasons, resort to picking fights with out-groups to divert people. Much of Germany’s military-industrial elite saw nationalist diversions as crucial to escape the terrifying spread of socialism before 1914.

I’m ignorant about all these dynamics in China but if forced to bet I would bet that Allison underplays these weaknesses and I would bet against another 20 years of straight line growth. In the spirit of Tetlock, I’ll put a number on it and say a 80% probability of a bad recession or some other internal crisis within 20 years that is bad enough to be considered ‘the worst domestic crisis for the leadership since Tiananmen and a prelude to major political change’ and which results in either a Tiananmen-style clampdown or big political change. (I have not formulated this well, suggestions from Superforecasters welcome in comments.)

Part of my reason for thinking China will not be able to avoid such crises is a fundamental dynamic that Fukuyama discussed in his much-misunderstood ‘The End of History’: economic development requires openness and the protection of individual rights in various dimensions, and this creates an inescapable tension between an elite desire for economic dynamism and technological progress viz competitor Powers, and an elite fear of openness and what it brings politically/culturally.

The KGB and Soviet military realised this in the late 1970s as they watched the microelectronics revolution in America but they could never develop a response that worked: they were very successful at stealing stuff but they could not develop domestic companies because of the political constraints, as Marshall Ogarkov admitted (off-the-record!) to the New York Times in 1983. China watched the Soviet Union implode and chose a different path: economic liberalisation combined with greater economic and information rights, but no Gorbachev-style political opening up. This caution has worked so far but does not solve the problem.

Singapore and China could not develop economically as they have without also allowing much greater individual freedom in some domains than Soviet Russia. Developing hi-tech businesses cannot be done without a degree of openness to the rest of the world that is politically risky for China. If there is too much arbitrary seizure of property, as in the KGB-mafia state of Russia, then people will focus on theft and moving assets offshore rather than building long-term value. Chinese entrepreneurs have to be able to download software, read scientific and technical papers, and access most of the internet if they are not to be seriously disadvantaged. China knows that its path to greatness must include continued growth and greater productivity. If it does not, then like other oligarchies it will rapidly lose legitimacy and risks collapse. This is inconsistent with all-out repression. It will therefore have to tread a fine line of allowing social unhappiness to be expressed and adapting to it without letting it spin out of control. Given social movements are inherently complex and nonlinear, plus social media already seethes with unhappiness in China, there will be a constant danger that this dynamic tension breaks free of centralised control.

This is, obviously, one of the many reasons why the leadership is so interested in advanced technology and particularly AI. Such tools may help the leadership tread this tightrope without tumbling off, though maintaining a culture at the edge-of-the-art in technologies like AI simultaneously exacerbates the very turbulence that the AI needs to monitor — there are many tricky feedback loops to navigate and many reasons to suspect that eventually the centralised leadership will blunder, be overwhelmed, collapse internally and so on. Can China’s leaders maintain this dynamic tension for another 20 years? As Andy Grove always said, only the paranoid survive…

3. Contrast between the EU and China

High-tech breakthroughs are increasingly focused in North East America (around Harvard), West Coast America (around Stanford), and coastal China (e.g Shenzhen). When the UK leaves the EU, the EU will have zero universities in the global top 20. EU politicians are much more interested in vindictive legal action against Silicon Valley giants than asking themselves why Europe cannot match America or China. On issues such as CRISPR and genetic engineering the EU is regulating itself out of the competition and many businesspeople are unaware that this will get much worse once the ECJ starts using the Charter of Fundamental Rights to seize control of such regulation for itself, which will mean not just more anti-science regulation but also damaging uncertainty as scientists and companies face the ECJ suddenly pulling a human rights ‘top trump’ out of the deck whenever they fancy (one of the many arguments Vote Leave made during the referendum that we could not get the media to report, partly because of persistent confusion between the COFR and the ECHR). Organisations like YCombinator provide a welcoming environment for talented and dynamic young Europeans in California while the EU’s regulatory structure is dominated by massive incumbent multinationals like Goldman Sachs that use the Single Market to crush startup competitors.

If you watch this documentary on Shenzhen, you will see parts of China with the same or even greater dynamism than Silicon Valley and far, far beyond the EU. The contrast between the reality of Shenzhen and the rhetoric of blowhards like Macron is one of the reasons why many massive institutional investors do not share CBI-style conventional wisdom on Brexit. The young vote with their feet. If they want to be involved in world-leading projects, they head to coastal China or coastal America, few go to Paris, Rome, or Berlin. The Commission publishes figures on this but never faces the logic.

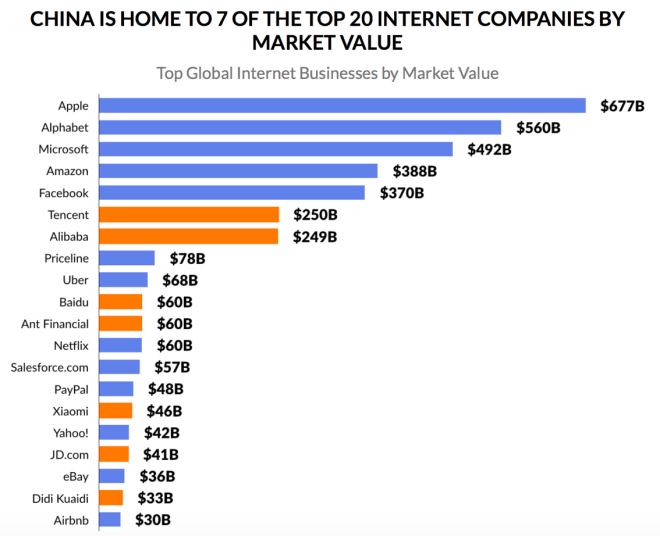

Chart: notice how irrelevant the EU is

We are escaping the Single Market / ECJ / Charter of Fundamental Rights quagmire that will deepen the EU’s stagnation (despite Whitehall’s best efforts to scupper the referendum). The UK should now be thinking about how we provide the most dynamic environment in Europe for scientists and entrepreneurs. After 50 years of wasting time in dusty meeting rooms failing to ‘influence’ the EU to ditch its Monnet-Delors plan, we could start building things with real value and thereby acquire real, rather than the Foreign Office’s chimerical, influence. Let Macron et al continue with the same antiquated rhetoric: we know what will happen, we’ve seen it since all the pro-euro forces in the UK babbled about the ‘Lisbon Agenda’ in 2000 — rhetoric about ‘reform’ always turns into just more centralisation in Brussels institutions, it does not produce dynamic forces that create breakthroughs and real value. Economic, technological, and political power will continue to shift away from an EU that cannot and will not adapt to the forces changing the world: its legal model of Single Market plus ECJ make fast adaptation impossible. We will soon be out of Monnet’s house and Whitehall’s comfortable delusions (‘special relationship’, ‘punching above our weight’) will fade. Contra the EU’s logic, in a world increasingly defined by information and computation the winning asset is not size — it is institutional adaptability.

Those on the pro-EU side who disagree with this analysis have to face a fact: people like Mandelson, Adair Turner, the FT, and the Economist have been repeatedly wrong in their predictions for 20 years about ‘EU reform’, and people like me who have made the same arguments for 20 years, and called bullshit on ‘EU reform’, have been repeatedly vindicated by actual EU Treaties, growth rates, unemployment trends, euro crises and so on. (The Commission itself doesn’t even produce fake reports showing big gains from the Single Market, the gains it claims are relatively trivial even if you believe them.) What is happening in the EU now to suggest to reasonable observers that this will change over the next 20 years? Every sign from Juncker to Macron is that yet again Brussels will double down on Monnet’s mid-20th Century vision and the entire institutional weight of the Commission and legal system exerts an inescapable gravitational pull that way.

4. ‘Anti-access / area denial’ (A2/AD)

One aspect of China’s huge conventional buildup is what is known as A2/AD: i.e building forces to prevent America intervening near China, using missiles, submarines, cyber, anti-space and other weapons. The US response is known as ‘AirSea Battle’.

I won’t go into this here but it is an interesting topic that is also relevant to UK defence debates. The transformation of US forces goes back to a mid-1970s DARPA project known as Assault Breaker that began a series of breakthroughs in ‘precision strike’ where computerised command and control combined with sensors, radar, GPS and so on to provide the capability for precise conventional strike. The first public demo of all this was the famous films in the first Gulf War of bombs dropping down chimneys. This development was central to the last phase of the Cold War and the intolerable pressure put on Soviet defence expenditure. Soviets led the thinking but could not build the technology.

One of the consequences of these developments is that aircraft carriers are no longer safe from cheap missiles. I started making these arguments in 2004 when it was already clear that the UK Ministry of Defence carrier project was a disaster. Since then it has been a multi-billion pound case study in Whitehall incompetence, the MoD’s appalling ‘planning’ system and corrupt procurement, and Westminster’s systemic inability to think about complex long-term issues. Talking to someone at the MoD last year they said that in NATO wargames the UK carriers immediately bug out for the edge of the game to avoid being sunk. Of course they do. Carriers cannot be deployed against top tier forces because of the vast and increasing asymmetry between their cost and vulnerability to cheap sinking. Soon they will not be deployable even against Third World forces because of the combination of cheap cruise missiles and exponential price collapse and performance improvement of guidance systems (piggybacking the commercial drone industry). Soon an intelligent terrorist with a cruise missile and some off-the-shelf kit will be able to sink a carrier using their iPhone: see this blog for details. The MoD has lied and bluffed about all this for 20 years, this Government will continue the trend, and the appalling BAE will continue to scam billions from taxpayers unbothered by MPs.

5. Strategy, Sun Tzu and Bismarck: Great Powers and ‘the passions of sheep stealers’

China is the home of Sun Tzu. His most famous advice was that ‘winning without fighting is the highest form of warfare’ — advice often quoted but rarely internalised by those responsible for vital decisions in conflicts. This requires what Sun Tzu called ‘Cheng/Ch’i’ operations. You pull the opponent off balance with a series of disorienting moves, feints, bluffs, carrots, and sticks (e.g ‘where strong appear weak’). You disorient them with speed so they make blunders that undermine their own moral credibility with potential allies. You try to make the opponent look like an unreasonable aggressor. You isolate them, you break their alliances and morale. Where possible you collapse their strategy and will to fight instead of wasting resources on an actual battle. And so on…

Looking at the US-China relationship through the lens of ‘winning without fighting’ and nuclear risk suggests that the way for America to ‘win’ this Thucydidean struggle is: ‘don’t try to win in a conventional sense, but instead redefine winning’. Given the unlimited downside of nuclear war and what we now know about the near-disasters of Cold War brinkmanship, it certainly suggests focus on the goal of avoiding escalating crises involving nuclear weapons, and this goal has vast consequences for America’s whole approach to China.

Allison’s ideas about how the US might change strategy are interesting though I think his ‘academic’ approach is too rigid. Allison suggests distinct strategies as distinct choices. If one looks at the world champion of politics and diplomacy in the modern world, Bismarck, his approach was the opposite of ‘pick a strategy’ in the sense Allison means. Over 27 years he was close to and hostile to all the other Powers at different times, sometimes in such rapid succession that his opponents felt badly disoriented as though they were dealing with ‘the devil himself’, as many said.

Bismarck contained an extremely tyrannical ego and an even more extreme epistemological caution about the unpredictability of a complex world and a demonic practical adaptability. He knew events could suddenly throw his calculations into chaos. He was always ready to ditch his own ideas and commitments that suddenly seemed shaky. He was interested in winning, not consistency. He had a small number of fundamental goals — such as strengthening the monarchy’s power against Parliament and strengthening Prussia as a serious Great Power — which he pursued with constantly changing tactics. He was always feinting and fluid, pushing one line openly and others privately, pushing and pulling the other Powers in endless different combinations. He was the Grand Master of Cheng/Ch’i operations.

I think that if Bismarck read Allison’s book, he would not ‘pick a strategy’. He would use many of the different elements Allison sketches (and invent others) at the same time while watching China’s evolution and the success of different individuals/factions in the governing elite. For example, he would both suggest a bargain over dropping security guarantees for Taiwan and launch a covert (apparently domestic) cyber campaign to spread details of the Chinese leadership’s wealth and corruption all over the internet inside ‘the Great Firewall’. Carrot and stick, threaten and cajole, pull the opponent off balance.

I think that Bismarck’s advice would be: get what you can from dropping the Taiwanese guarantees and do not create nuclear tripwires in Korea. He was contemptuous of any argument that he ought to care about the Balkans for its own sake and repeatedly stressed that Germany should not fight for Austrian interests in the Balkans despite their alliance. He often repeated variations on his famous line — that the whole of the Balkans was not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier. Great Powers, he warned, should not let their fates be tied to ‘the passions of sheep stealers’. On another occasion: ‘All Turkey, including the various people who live there, is not worth so much that civilised European peoples should destroy themselves in great wars for its sake.’ At the Congress of Berlin, he made clear his priority: ‘We are not here to consider the happiness of the Bulgarians but to secure the peace of Europe.’ A decade later he warned other Powers not to ‘play Pericles beyond the confines of the area allocated by God’ and said clearly: ‘Bulgaria … is far from being an object of adequate importance … for which to plunge Europe from Moscow to the Pyrenees, and from the North Sea to Palermo, into a war whose issue no man can foresee. At the end of the conflict we should scarcely know why we had fought.’

In order to avoid a Great Power war he stressed the need to stay friendly with Russia, and the importance of being able to play Russia and Austria off against each other, France, and Britain: ‘The security of our relations with the Austro-Hungarian state depends to a great extent on our being able, should Austria make unreasonable demands on us, to come to terms with Russia as well.’ This was the logic behind his infamous secret Reinsurance Treaty in which, unknown to Austria with which he already had an alliance, Germany and Russia made promises to each other about their conduct in the event of war breaking out in different scenarios, the heart of which was Bismarck promising to stay out of a Russia-Austria war if Austria was the aggressor. In 1887 when military factions rumbled about a preventive war against Russia to help Austria in the Balkans he squashed the notion flat: ‘They want to urge me into war and I want peace. It would be frivolous to start a new war; we are not a pirate state which makes war because it suits a few.’ Preventive war, he said, was an egg from which very dangerous chicks would hatch.

His successors ditched his approach, ditched the Reinsurance Treaty, pushed Russia towards France, and made growing commitments to support Austria in the Balkans. This series of errors (combined with Wilhelm II’s appalling combination of vanity, aggression, and indolence which is echoed in a frightening proportion of leading politicians today) exploded in summer 1914.

Would Bismarck tie the probability of nuclear holocaust to the possibilities for extremely fast-moving crises in the South China Seas and ‘the passions of sheep stealers’ in places like North Korea? No chance.

Instead of taking the lead on Korea, I suspect Bismarck’s approach would be to go quiet publicly other than to suggest that China has a clear responsibility for Kim’s behaviour while perhaps leaking a ‘secret’ study on the consequences of Japan going nuclear, to focus minds in Beijing. Regardless of whose ‘fault’ it is, if the situation spirals out of control and ends with North Korea, perhaps because of collapsed command and control empowering some mentally ill / on drugs local commander (America has had plenty of those in charge of nukes) killing millions of Koreans and America destroying North Korea, who thinks this would be seen as a ‘win’ for America? Trump’s threats are straight out of the Cold War playbook but we know that playbook was dodgy even against the relative ‘rationality’ of people like Brezhnev and Andropov, never mind nutjobs like Kim…

So: avoid nuclear crises. Therefore do not give local security ties to Taiwan and Korea that could trigger disaster. What positive agenda can be pushed?

America should seek cooperation in areas of deep significance and moral force where institutions can be shaped that align orientation over decades. Three obvious areas are: disaster response in Asia (naval cooperation), WMD terrorism (intel cooperation), and space. China already has an aggressive space program. It has demonstrated edge-of-the-art capabilities in developing a satellite-based quantum communication network, a revolutionary goal with even deeper effects than GPS. It will go to the moon. The Cold War got humans onto the moon then perceived superiority ended American politicians’ ambition. Instead of rebooting a Cold War style rivalry, it would be better to try to do things together. One of the most important projects humans can pursue is — as Jeff Bezos has argued and committed billions to — to use the resources of space (which are approximately ALL resources in the solar system) to alleviate earth’s problems, and the logic of energy and population growth is to shift towards heavy manufacturing in space while Earth is ‘zoned residential and light industrial’. Building the infrastructure to allow such ambition for humanity is inherently a project of great moral force that encourages international friendship and provides an invaluable perspective: a tiny blue dot friendly to life surrounded by vast indifferent blackness. People can be proud of their nation’s contributions and proud of a global effort. (As I have said before, contributing to this should be one of the UK’s priorities post-Brexit — how much more real value we could create with this than we have in 50 years with the EU, and developing the basic and applied research for robotics would have crossover applications both with commercial autonomous vehicles and the military sphere.)

Of course, there must be limits to friendly cooperation. What if China takes this as weakness and increasingly exerts more and more power, direct and indirect, over her neighbours? This is obviously possible. But I think the Bismarck/Sun Tzu response would be: if that is how she will behave driven by internal dynamics, then let her behave like that, as that will do more than anything you can do to persuade those neighbours to try to contain China. Trying to contain China now won’t work and would be seen not just in China but elsewhere as classic aggression from an imperial power. China is neither like Hitler’s Germany nor Stalin’s Soviet Union and treating it as such is bound to provoke intense and dangerous resentment among a billion people who suffered appallingly for decades under Mao. But if America backs off and makes clear that she prefers cooperation to containment, and then over time China seeks to threaten and dominate Japan, Australia and others, then that is the time to start building alliances because that is when you will have moral authority with local forces — the vital element.

A Bismarckian approach would also, obviously, involve ensuring that America remains technologically ahead of China, though this is a much more formidable task than it was with Russia and that was seen for a while (after Sputnik) as an existential challenge (and famous economists like Paul Samuelson continued to predict wrongly that the Soviet economy would overtake America’s). Attempting to escape Thucydides means trying to build institutions and feelings of cooperation but it also requires that militaristic Chinese don’t come to see America as vulnerable to pre-emptive strikes. As AI, biological engineering, digital fabrication and so on accelerate, there may soon be non-nuclear dangers at least as frightening as nuclear dangers.

Finally, there is an interesting question of self-awareness. American leaders have a tendency to talk about American interests as if they are self-evidently humanity’s interests. Others find this amusing or enraging. Its leaders need a different language for discussing China if they are to avoid Thucydides.

Talented political leaders sometimes show an odd empathy for the psychology of opposing out-groups. Perhaps it’s a product of a sort of ‘complementarity’ ability, an ability to hold contradictory ideas in one’s head simultaneously. It is often a shock for students when they read in Pericles’s speech that he confronted the plague-struck Athenians with the sort of uncomfortable truth that democratic politicians rarely speak:

‘You have an empire to lose, and there is the danger to which the hatred of your imperial rule has exposed you… For by this time your empire has become a tyranny which in the opinion of mankind may have been unjustly gained, but which cannot be safely surrendered… To be hateful and offensive has ever been the fate of those who have aspired to empire.’ Thucydides, 2.63-4, emphasis added.

Bismarck too didn’t fool himself about how others saw him, his political allies, and his country. He much preferred boozing with revolutionary communists than reactionaries on his own side. When various commercial interests tried to get him to support them in China, he told the English Ambassador crossly:

‘These blackguard Hamburg and Lubeck merchants have no other idea of policy in China but to, what they call ‘shoot down those damned niggers of Chinese’ for six months and then dictate peace to them etc. Now, I believe those Chinese are better Christians than our vile mercantile snobs and wish for peace with us and are not thinking of war, and I’ll see the merchants and their Yankee and French allies damned before I consent to go to war with China to fill their pockets with money.’

There are powerful interests urging Washington to aggression against China. The nexus of commercial and military interests is always dangerous, as Eisenhower famously warned in his Farewell Speech. They will be more dangerous as jobs continue to shift East driven by markets and technology regardless of Trump’s promises. The Pentagon will overhype Chinese aggression to justify their budgets, as they did with Russia.

Bismarck was a monster and the world would have been better if one of the assassination attempts had succeeded (see HERE for other branching histories) but he also understood fundamental questions better than others. Those responsible for policy on China should study his advice. They should also study summer 1914 and ponder how those responsible for war and peace still make these decisions in much the same way as then, while the crises are 1,000 times faster and a million times more potentially destructive.

Such problems require embedding lessons from effective institutions into our systematically flawed political institutions. I describe in detail the systems management approach to complex projects developed in the 1950s and 1960s that is far more advanced than anything in Whitehall today and which is part of necessary reforms (see HERE, p.26ff for summary of lessons). I will blog on other ideas. Unless we find a way to build political institutions that produce much more reliable decisions from the raw material of unreliable humans the law of averages means we are sure to fall off our tightrope, and unlike in 1918 or 1945 we won’t have anything to clamber back on to…

“So: avoid nuclear crises. Therefore do not give local security ties to Taiwan and Korea that could trigger disaster.”

Doesn’t this probably result in the invasion of Taiwan by China and South Korea by the North? Is this a fair swap for reducing still further the probability of a nuclear strike on the American mainland?

Does this also apply to the US/UK presence in Eastern Europe?

LikeLike

I was surprised at your non-U.K EU university ranking statistic… I checked and according to the latest 2018 QS World University Rankings you were being kind: the top EU university outside the U.K. is the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris at #43 – down from #33 in 2017. Interesting to note that 7 of the 10 universities overtaking ENS last year are Asian.

LikeLike

An excellent piece. I share your irritation about Allison’s interpretation of Thucydides, but agree this is only a quibble – “Thucydides Trap” is a convenient label, not part of an actual attempt to understand the Peloponnesian War!

Are you familiar with Deming? In his terms, the Bismarckean approach is about laserlike constancy of Purpose combined with extreme flexibility of Method. The opposite of the way most Western organisations (public or private sector) operate today – they display inflexibility of Method (despite frequent reorganisations and a constant infusion of new fads) combined with extreme vagueness about Purpose (despite a plethora of mission statements, straplines, strategies, etc. – most of which obfuscate rather than clarify Purpose).

The tragedy is that we listened to Drucker, not Deming, and his Management by Objectives is so universalised and internalised that people cannot even see it as a system that one might stand outside, critique and improve (or – better – replace). They literally cannot conceive of any other way of running things. Yet this system is implicated in innumerable public and private failures (e.g. Iraq in all its aspects, the Financial Crash and the associated failure of regulation, etc. etc.).

Deming of course is famous as progenitor of the Toyota System, but that doesn’t really do him justice, because the T.S. itself became a fashionable fad a few years ago, resulting lots of stupid attempts to import it wholesale into areas quite different from car manufacturing, and on the basis of a very superficial understanding. The inevitable failure of this fad discredited the T.S. (and perhaps Deming too). And Toyota itself has moved away from Deming and as result – surprise! – been afflicted by some of the problems that afflict other companies. But instead of drawing the obvious conclusions, the reaction is, “See, I always said that Toyota-Deming stuff was overrated.” Is it not amazing how people/organisations immunise themselves against challenges to the status quo?

Lots of common ground between Deming and Colonel Boyd.

“They had, of course, strong bureaucratic reasons to do so: a more dangerous enemy was the best argument for more funding. It is important to keep in mind this potential error viz China.”

Funding aside, there is always the (unvoiced) assumption (and all the more dangerous for being unvoiced) that giving most weight to the worst case scenario is the safest course. As the Iraqi W.M.D. debacle shewed, this is not true: it got us into a disastrous war (the Butler report makes this quite clear, but it’s not an aspect that is ever commented upon – just vague stuff about the “dangers of groupthink”).

LikeLike

And of course extreme constancy of purpose combined with flexibility of method is a characteristic of criminals, hackers and terrorists.- supreme examples of emergent, adaptive, self-organising threats.

There is a certain grim amusement from hearing e.g. military commanders when after months (if not years) they have finally countered a particular Taliban tactic they say, “We have forced them to change their approach. This shews we are winning.” No it shews *they* are winning. Adaptation is what they do, they are doing it now, and how long will it take you to devise a response to their new tactics?

LikeLike

Hi Dom, I genuinely enjoy reading your posts but it takes me a months to read them. First, I read it through and ruminate on parts. Then I read them from start to finish again. Then I try and dissect different areas and ponder them, rereading… My head hasn’t had to work this hard in years. Thank you (not for everything!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, imagine how badly my head struggles…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think you are right to assume that China will not continue a straight line trajectory from here. Not only do they have to walk the tightrope you describe, but there is also the age old problem of controlling turf wars within the people’s republic. All nations have their internal fault lines, but China has massive divides between its major cities and regions, which speak different languages and cleave to different cultures. Shenzhen is viewed with deep distrust by those in other parts of China. Guangdong province is seen as the Wild West: out of control metaphorically and all-too-often literally. The proximity to Hong Kong is part of it of course. Beijing has one view of this – Shenzhen was deliberately given certain freedoms – but other cities and regions are more green-eyed. The Shanghainese in particular resent the way Southern China gets away with a casual attitude to Beijing which would not be tolerated from any other region. And of course when some regions outstrip others, it can lead to real problems. I suspect that when some regions outstrip others technologically and educationally it is even more problematic than economic divides. Its a problem for the Chinese Government when the Chinese peasantry starves, but they are very used to covering that up and getting on with it. It will be rather more of a problem when a industrialised semi-educated urban workforce in places like Chengdu finds itself on the scrapheap, as we have to assume many will be.

LikeLike

Let’s nor forget that emergence of China is also rapidly undermining international trade system (Trump doesn’t help of course but that is likely temporary setback where China is permanent). China’s policy is and always (since 1980’s that is) was enlightened mercantilist, by which I mean the fact that China does not simply seek to block access to its market to protect its own companies but instead uses is as a trump card to trade for access. China’s position generally is that the benefits of trade should be relatively even and since China’s market is larger then others’, partners should open their markets more than China in any trade deal, with smaller economies suffering more (having less access or being forced to open more) than larger economies. Of course this policy is flexible and adjusted depending on any geopolitical needs of China. It is diametrically opposed to what pre-Trump used to be US policy for the last 70 years (which for what it’s worth wasn’t particularly beneficial to US economic interests but was extremely good for the rest of the West and East Asia, driven primarily by desire to spread/establish universalist (Wilsonian) ideals of US elite around the globe). The multilateral system worked especially well for small countries (think of emergence of rich city states – a feature not that prevalent before 1945) but it’s usefulness may be now limited since enforcement will likely be increasingly lackluster. That leads me to think that any smaller countries without (or even with – as renegotiations may be frequent) extensive bilateral trading arrangements will face serious challenges in the future and the large countries/economies will gain in relative competitiveness. Any US cooperation with China may actually increase the chances of this transpiring.

LikeLike